nigel, l

(article, Ellen Kanner)

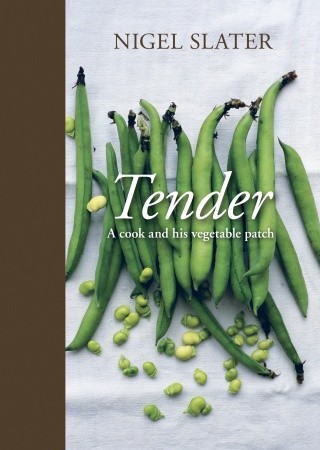

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] p(blue). “I was just born to cook,” says Nigel Slater. True, but he was also born to write. Equal parts M.F.K. Fisher and Billy Collins, Slater is the author of nine cookbooks, the essay collection Eating for England, and Toast, a Proustian, flavor-driven memoir made into a BBC film in which Slater himself has a bit part. He is the culinary host of the BBC series '"Simple and has penned a weekly food column in The Observer since 1993. p(blue). “The column is a bit of a confessional as much as it is a recipe column,” says Slater. “It’s not about a recipe; it’s bringing everything in. It’s our whole lives.” This approach defines Slater, who after over two decades of preparing food and writing about it still calls himself an amateur cook. He is an amateur in the true sense of the word — its origin comes from the Latin word meaning "to love." [%image nigel float=right width=300 caption="Nigel Slater"] p(blue). In his book Tender, Slater writes of his fondness for growing vegetables in his small urban garden and how he lovingly prepares them. In a companion book to Tender, just released here as Ripe: A Cook in the Orchard, he gives fruit the same devotion, writing about it in a way that makes the ordinary extraordinary. For most food writers, a plum-pie recipe is about crust and filling. Only Slater can describe the point where the underside of the pastry crust meets the fruit as the “bliss point.” You’re still writing a weekly food column for The Observer. Glancing at last Sunday’s column, I see you’re just as devoted to it as ever. What keeps it new for you? I can’t sometimes imagine why I am still, all these years on, excited and interested in food. I wouldn’t say I’m passionate about it, just quietly interested in food. It amazes me I’m still interested. It’s not just the food on the plate; there is so much more involved, not just in cooking something but in eating it, who you’re cooking it for, a meal you’re sharing. I’ve always concentrated on the minutiae of cooking, the little moments and details that take cooking from being something we do to being a pleasure and a joy. I don’t know if I can write a sensible paragraph about the food system, but I can write a thousand words about syrup falling off a spoon. I back off from the whole broad aspect of it, the politics, the whys and wherefores. I concentrate on the details. It’s not very fashionable, but I like food, I like the feel of it, the smell of it. I like the feel of food in the mouth. It can be comforting, exciting, even dangerous if it’s chile or ginger or a food you don’t know very well. I still get into raptures about it, because I’m a little bit greedy. How, after 19 years, can you still consider yourself an amateur cook? I don’t have my own restaurant. I’d always wanted to be a professional chef; then, when I got into professional kitchens, I realized I might be able to cook, but I wouldn’t be a very good chef. It’s a team thing, and I’m not a team player; I’m very much a loner. It’s not my thing at all. I was completely useless. I didn’t like the whole chef’s life. I failed there. I knew my future had to be food; that was what my true interest and true love was. I was lucky, really, I got into writing. I still think of myself as a home cook. I don’t think there’s anything professional about the way I cook. If I’m making a patisserie or something, it’ll be wobbly, the edges might be a little burned. It’s not going to look like a superb patisserie in town; it’s going to look home-cooked. I made it with love, but it doesn’t look professional. The good thing is, if it looks less intimidating, then people will have a go. I’m a home cook just doing my thing. You may still consider yourself a home cook but you got to play a professional chef in the film "Toast." How did that feel to you? The moment I put on the chef’s trousers, the chef’s jacket, and the hat, I suddenly felt so uncomfortable. I knew I’d made absolutely the right decision in not being a professional chef. It just feels wrong. Partly it was the clothes; I felt like I was in disguise, dressed as a chef. Then the fact there were too many people — there were all these people — that’s not what I want. It was a great relief when I could take the clothes off, take the microphone off, and walk away. In The Kitchen Diaries, you write that the pleasure of eating and the success of cooking comes of choosing the moment when “the food, the cook, and the time of year are at one with each other.” You mention your garden there and, of course, in Tender and Ripe, but your sense of sourcing and cooking and being one with the seasons was not as evident in Toast, if I recall. How and when did that develop for you? The thing about the food in Toast — it wasn’t directly after the war, but what we ate, what my parents were cooking, was very 1950s, even though I was brought up in the 1960s. White processed sliced bread was this thing from heaven. I did eat a lot of processed food as a child. [%image tender float=left] When I bought my first little flat, I didn’t have my own garden. I had a shared backyard and couldn’t grow anything, just a few things in pots like tomatoes and courgettes. It was when I bought my first little house that had its own garden that I realized I didn’t want a big green grass lawn to mow; I wanted to actually grow things. I dug up the lawn. I looked at it and thought, "I’m going to have a go at planting vegetables and planting fruit." What has your Tender experience growing fruit and vegetables taught you? It’s taught me you don’t have to follow the rules. The thing about growing things is, you look at a lot of gardening books, they’re beautifully written and very helpful. They do say there are certain rules — plant vegetables so many inches apart or plant at certain times of year. My garden’s growing space is quite small; I haven’t got the luxury of 12 inches between my carrots. They survive, and they’re fine. I know my tomatoes shouldn’t be planted in the same patch every year, but I do. It’s the sunniest place in the garden. You can break the rules and get away with it. But you do that with your cooking. On "Simple Suppers" and in your books, you have this sense of, "Oh, if you can’t find that, use this." So maybe what you learned in the garden you’ve naturally put into practice in the kitchen? I’ve always gotten away with things. I’m not a great one at planning my shopping. I open the fridge and, heavens, what on earth am I going to do with this? Somehow I get away with it. I don’t know; the angels are on my side. I’m not saying I haven’t made some mistakes, but at the end of the cooking, this is really quite nice. I guess I apply that approach to gardening, cooking, to growing things, that’s how it is — I just get away with it. [%image ripe float=right] Tender and Ripe make your little garden sound like Eden. But is there anything you’ve been lusting to grow that’s impossible in your climate? Not impossible but very, very difficult is sweet corn. The problem is we don’t have enough sun at the end of the summer. You put it in and you think it’s really growing well, we have enough rain and it’s plump, but there is rarely summer interval sunshine. I read that Alice Waters is so passionate about picking corn and picking it quickly, and I’ve never felt I got it truly right. I would love to go out to the garden and pick that corn. As Tolstoy famously wrote, '"Happy In Toast, you write of your own particular unhappiness after your mother died and credit it as the reason you turned to cooking. What made food the answer for you, rather than the usual teenage sources of solace, like rock or drugs or football? It was the answer from a very young age. I didn’t really know where to turn; I was suddenly alone and did not have anybody I felt could understand what I was going through. I couldn’t talk to my father. I found him quite intimidating, I couldn’t talk to him, but food — this was the answer. When I put those marshmallows in my mouth or ate some sweets, it’s like hugging a hot-water bottle. It makes you feel good. I never really strayed from that to this day. I treat food as comfort; always have, always go back. I fight against eating too much sugar and too many sweet things, but deep down that is to me the most comforting thing of all. It just puts the world to rights. You often write about the pleasure you get cooking for others. How do you feel about cooking for yourself? I love it. It’s just become such a part of my life, to go to the butcher, fishmonger, go to my cupboards. I don’t think of the alternatives, and there are some good alternatives. Great takeaway — a great Japanese meal, a pizza — never crosses my mind. I don’t cook for myself with any great feeling of "I must do this, otherwise I’m letting myself down." I was just born to cook something. So what might a happy-making April meal for yourself be? April’s one of those funny months. In theory, everything should be happening, but I find it isn’t. It’s difficult. You never know what the weather’s going to be. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipe ]] A happy-making meal for me in April is going to be pasta, with a little bit of cream, a little bit of lemon juice, and something from the garden — the first of my herbs coming up, some fresh mint in there or a little bit of tarragon, maybe some chives. Fettucine or pappardelle with that slight spring freshness of the herb and lemon. There would be a little dessert. There would be not a lot around in the way of fruit. I’d be tempted to have a go at something like a carrot cake or beetroot cake; we’ve still got that around in April, so I might do a chocolate beetroot cake. Chocolate’s always good. April’s my birthday, and this year it’s falling at Easter, so it would be something chocolatey. p(bio). Florida-based writer Ellen Kanner keeps a website and a blog and contributes regularly to the Huffington Post.

nigel, l

reference-image, l

ripe, l

tender, l