reference-image, l

(article, Shoshanna Cohen)

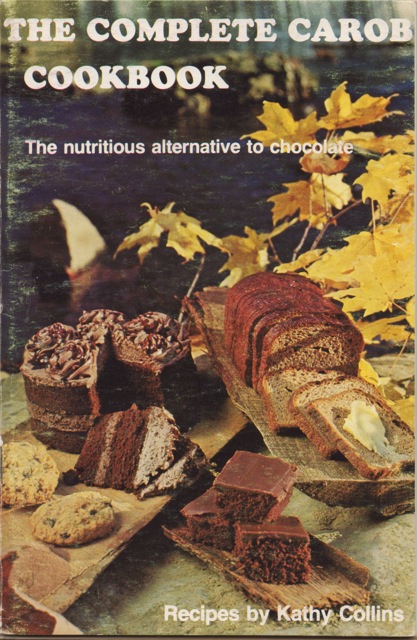

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] Let’s get something out of the way: Carob is absolutely not chocolate, nor is it fit to replace it. Shefali Kulkarni, in an article in the Spokane Spokesman-Review from 2006, calls it '"the and I can’t think of a more apt comparison. Both carob and tofu have a reputation of being healthful and gross, neither of which is necessarily true of either substance. Both have been hyped as better alternatives to other foods — chocolate and meat, respectively — and neither creates a convincing imitation. Both were big in the 1970s and have since fallen out of favor. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipe]] Apart from agedashi tofu and the bizarre appeal of cold, raw tofu eaten right out of the container, I see little reason to rally to the defense of clammy, spongy bean curd. Carob, however, is another matter. Carob gets a bad rap for being touted as a chocolate analogue, a dangerous proposition considering the militant devotion of chocoholics. As any one of them will tell you, there is no substitute for the real thing. Sure, carob has a deep, smooth flavor with a touch of acidity. This puts it in the same category as chocolate and coffee, much in the way that Dick Cheney, Michael Cera, and Muhammad Ali are all categorized as men. Carob tastes completely different from chocolate and doesn’t have the same feel-good chemicals. I’m not saying carob is the Dick Cheney of chocolate. But taken on its own merit, which nobody does, carob is marvelous and intriguing, with a personality of its own. [%image reference-image float=right width=400 caption="Carob chips may look like chocolate chips, but don't let that fool you."] Carob also gets a bad reputation by being abused by hippies who bake it into healthy “treats” involving too much wheat germ, whole-wheat flour, and even black beans, and not nearly enough heavy cream, egg whites, and butter. Carob was embraced by health foodies in the 1970s and 1980s, who proclaimed it to be lower in fat and higher in nutrients than junk-foody chocolate. Of course, trends in nutrition change just as quickly as trends in fashion, and eventually people figured out that, mixed with fats and sugars and baked into cookies, carob isn’t much healthier than chocolate after all. While carob’s natural sweetness lets a cook use less refined sugar, baked goods containing chocolate and carob are essentially on par — and carob doesn’t make everything better when you have PMS. We also learned that chocolate is actually good for you (antioxidants!), and that was the final nail in carob’s coffin of irrelevance. These days in the U.S., you typically see it only in natural-food stores, the graveyard of passé health trends. Next to the sunflower seeds and soy jerky in the bulk aisle, you may find carob peanut clusters. In the freezer aisle, you might discover carob-covered rice-cream sandwiches (which sound like something I made up for the purpose of this story, but they do exist, and I swear, don’t knock ‘em till you try ‘em). I have no idea who else eats this stuff, because everyone I know proclaims to hate carob. Yet somehow it remains in production. Perhaps because I grew up in Berkeley in the 1980s, I always ate and liked carob, and continued to do so here and there as an adult. But when I stopped eating chocolate was when carob and I really renewed our relationship. That’s right, I don’t eat chocolate. Call the Times. A couple of years ago, I stopped drinking coffee because it turned me into a twitchy, high-strung sociopath, and I found that I was suddenly inordinately sensitive to trace amounts of caffeine and theobromine, the related substance that you find in chocolate. If I was in '"Mystery this sensitivity would be my superpower. If I drank a cup of decaffeinated tea or ate a couple of Newman O’s, I’d be up all night. So I cut out decaf and chocolate, too, joining the ranks of white people with high-maintenance, self-imposed dietary restrictions. It isn’t the terrifyingly big deal that people imagine. While I always enjoyed chocolate, I was never a chocolate person, the kind who moan erotically when they talk about it. I liked it because it was sweet, rich, and creamy. No chocolate? Fine. There are plenty of other sweet, rich, creamy things to devour. Cocoa-free white chocolate. Peanut butter. Carob. Carob, a fleshy brown pod that grows on trees (often in pleasant neighborhoods of southern California, incidentally), originated in the Levant, and various Mediterranean peoples began cultivating it as soon as they could figure out how, probably in the first millennium B.C., according to the page-turner Domestication of Plants in the Old World, by Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf. In Nectar & Ambrosia: An Encyclopedia of Food in World Mythology, author Tamra Andrews tells us that this magical fruit shows up in the Bible and its various collections of side comments (the Mishnah, the Talmud, etc.), as well as in mythology both Mesopotamian and South American — carob somehow made it there, too. Jews eat it on Tu Bishvat (Tree Day), and Arabs drink carob juice during Ramadan. As the carob tree is an evergreen, and its fruit rich in vivifying carbohydrates, it has often served as a symbol of immortality, writes Andrews. It is sometimes called St. John’s bread, because he snacked on it when he was hanging out in the desert. [%image carobbook float=right width=300] The Internet tells me that people in the Middle East make carob molasses by soaking carob in water and reducing the extraction. You mix it with tahini and eat it on toast. There is also something called pekmez, which as far as I can ascertain is the same thing in its Turkish iteration, sometimes made from carob, sometimes from other stuff, and taken as medicine. When the Bible talks about “honey,” it might really be carob molasses — for more on that subject, see Phyllis Glazer’s recent honey article in the Los Angeles Times, which also includes some good-looking recipes. Like chocolate and coffee, carob is excellent in sweets. With a little tinkering to compensate for its unique sugar levels (high) and consistency (somewhere between chocolate and coffee on the melty-grainy continuum), it can be successfully plugged into many traditional recipes with excellent results. Deep in the vaults of the Multnomah County Library — so deep that a page had to be sent to retrieve it, which makes me think it wasn’t checked out since before the Atkins diet — I found a beautiful gem: The Complete Carob Cookbook, written by Kathy Collins and apparently published by her family way back in 1981. The author explains, in dubiously uncited claims, carob’s purported health benefits (“better for diabetics and individuals with acne problems” than chocolate) and gives a few dozen ways to prepare it. This is my favorite kind of DIY cookbook, because rather than being sharply branded and marketed, it shows the author's roots. It’s full of the health-foody techniques and values that were in vogue at the time of its publication, but also reveals the down-home way Kathy Collins must have grown up cooking. Like the 1978 Betty Crocker cookbook, it is a product of its time. In that world, chocolate is evil, but trans fats are A-OK because nobody knows what they are yet. The cookbook has recipes for sunflower-wheat germ-carob “health cookies” and sun-cooked carob cake made with raisins and raw grains, but also carob Bavarian cream and carob Texas sheet cake. [%image pie float=right width=400 caption="Cohen's rendition of carob mousse pie."] Before I read this book, I had never seen carob and Cool Whip in the same recipe. Both appear in Collins’ carob mousse pie, which I predictably couldn’t pass up. The result was a smooth, creamy slice that would seem normal at a suburban barbecue if you didn’t know what was in it, a great example of how carob can step out of the shadow of its reputation and shine as a legitimate, fresh flavor for conventional desserts. Why should vanilla, chocolate, almond, and lemon have all the fun? Carob is unexpected, but no weirder or more assertive than root beer, a common dessert flavor that if you think about it is incredibly weird. I also tried Collins’ carob pudding cake. Rich, dense, and dark with not a lot of dairy, this one shows off carob’s subtle bitter and citrusy notes. In the oven, the batter separates into two layers: a dense cake resting on a quarter-inch of pudding-like sauce, which you spoon over the top. I had never made a pudding cake before, and I thought it was amazing. (I am easily amused.) This recipe is very sweet and would be good paired with tart frozen yogurt or fruit. I’m not done experimenting with carob. I want to try that Texas sheet cake, and it seems as if carob would also lend itself well to savory applications like mole, chile, meat stew, or Moroccan chicken with dried fruit. Maybe I’ll bring some pods with me on my next half-marathon. Have you cooked or baked with carob? Do you love it or hate it? I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. Just don’t try to tell me that it’s just like chocolate.

reference-image, l

pie, l

carobbook, l