reference-image, l

(article, Ellen Kanner)

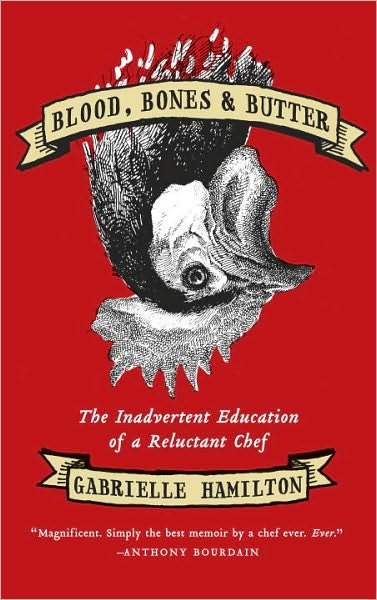

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] p(blue). Back in 1999, Gabrielle Hamilton — the winner of this year’s James Beard Award for Best New York Chef — opened a tiny East Village restaurant called Prune. (The fruit was her childhood nickname.) Bucking the 1990s trend of big, barnlike restaurants, vertical plates, and caviar on everything rarefied, Hamilton’s 30-seat eatery served up the simple, elemental dishes she loved, the food she'd grown up eating. And she’s been doing it now for more than a decade — which in New York restaurant time, you can figure in dog years. p(blue). In addition to the grueling task of running a restaurant, Hamilton — who studied at the Iowa Writers' Workshop and earned an MFA in fiction from the University of Michigan — somehow found time to write, contributing regularly to the New York Times food section as well as assorted food magazines. Last year, the chef and mother of two dazzled the foodie world with her memoir, Blood, Bones & Butter, which the chef and writer Anthony Bourdain called “simply the best memoir by a chef ever.” [%image reference-image float=right width=400 caption="Gabrielle Hamilton at work."] p(blue). In Blood, Bones & Butter, Hamilton reveals the forces that shaped her: her French mother, a kitchen goddess in black eyeliner, and her American father, a dreamer and a set designer who showed his children “how to create beauty where none existed, how to be generous beyond our means, how to change a small corner of the world just by making a little dinner for a few friends. From him we learned how to make and give luminous parties.” p(blue). The book also details Hamilton's naughty, gritty, druggy years; there’s a reason Hamilton subtitles her book "The Inadvertent Education of a Reluctant Chef." But mostly, Blood, Bones & Butter explains how Hamilton made Prune the oasis it is. It’s about feeding the hunger in the soul as well as the hunger in the belly. Congratulations on winning the James Beard Award. How big a deal is that for you? My sister \[Melissa Hamilton, the co-founder and publisher of The Canal House Cooking series\] and I have this joke: when you’re not nominated, you think, what a silly organization and who cares about that silly party? And then you get invited and it’s a lovely party and what an important institution this is. I'm very happy to be invited to the party. I don’t know how the Beard Awards work; I’m just grateful. You’ve been running Prune for nearly a dozen years. How has your approach to food changed since opening the restaurant? It hasn’t. I had done catering and food styling and recipe testing, and when I opened the restaurant, I got to cook food like I grew up eating. It has not changed at all since the big opening — that’s where we are and where it stays. For a period there, I thought, "Oh my God, am I going to have to get into this molecular-gastronomy crap?" I’m susceptible like anyone else. I think I’m supposed to do what’s hot and now. Fortunately, I’ve never succumbed. Molecular is not on its way out, but the path is splitting. A huge school is abandoning the chemical manipulation and getting basic and technique-driven. It’s nice for me to stay on this path, nice to see if you put your head down and do your job, the winds will blow past you. I’m glad to see the world is coming back around. Having said that, I think we have a tendency to abandon things when they fall out of fashion. No one drinks merlot right now; it’s got a bad name. What’s wrong with good merlot? She’s not your friend anymore because she’s not in the hot crowd? Screw you, what kind of friend are you? You haven’t wanted to open up Prune Las Vegas? I understand the appeal of of scratching all your itches and opening a new place whenever you’re bored with the old one — it’s totally appealing. Sometimes I’m aching to take other parts of myself out for a walk. I don’t just know how to cook rustic American; I know how to do high-end, I know how to put dots on the plate, to have perfect china, whatever. I know how to cook with Asian ingredients, but I’m not allowed to do that. I can’t use galangal. I love caviar, too — it’s just not the restaurant I opened. What keeps it new for you? What keeps bringing you back to the kitchen? I really did see this place as a commitment, and as many people know who have gone through long relationships, there is a rich, rich, rich, deep satisfaction in longevity, in keeping a place fresh and alive after the second year, after the honeymoon fades. If you’re still combing your hair for a date 11 years down the road, that’s pretty good. I still give such a shit about it, it still matters so much to me. In Blood, Bones & Butter, you write so beautifully about what you cook and eat when you’re in Italy. What’s the difference between an Italian and an American food sensibility? Here, everyone’s watching the Food Network, or so everybody says. Everyone says they have cilantro and truffle oil, they’re equipping their kitchens with sous-vide machines. What’s to talk about, really, for so long and in so much depth and detail? I’m happy to talk about it for five minutes, but then I want to go on and eat my dinner. In Italy, everyone understands quite acutely the food is important to keep the people at the table, but the point is the people at the table and not the food. Did you sit down at the table as a family growing up, or was it your basic American grab-and-go? We sat around the table, we sat en famille. Much is made of that now. It sounds right and there have been studies about it, but I’m not so convinced. I think there are plenty of children who have access to OxyContin and get addicted even though they’re eating together, and conversely, there are families that grab and go and have their shit together. I’m unsold on this idea of the romanticism of the family table. And yet you create that at Prune. We make dinner for all the customers. That’s our part. Then they have to do the rest — bring the conversation and the right people. We provide the meal and the setting and do the dishes. Yeah, but in the book you write about wanting to provide food that more than satisfies a hunger, it gives a sense of being “picked up and fed . . . and feel warm with recognition.” What dish does that for you? It changes with season, weather, mood, with health, where I am — it changes each day of the year. It happens when the craving, the hunger is met perfectly. You want something warm and salty and you get warm and salty. You’re in the mood for cold and juicy, and you get cold and juicy. But if I have to name something, eggs are really where it’s at for me. [%image bookcover float=left width=200] Do you have a kitchen philosophy? I’m always made nervous when those two words are in the same sentence. Well, what about this: what’s the best thing you've learned in the kitchen? I learned autodidactically; no one taught it to me. I learned to not hope for the best, if that makes sense, to pay attention to what’s actually going on rather than what I wish was going on. As a younger cook, I would see something cooking in a pan — say, six pieces of fish. I’m watching three of them brown much darker than the other three. I’d go on, thinking this is going to come back together — miraculous! — they’re all going to come out at the same time. Now I say, Gabrielle, take the three pieces out that are getting darker than the other three. I’ve learned let’s not hope, but to stop and take care of it. What did you learn about yourself in writing Blood, Bones & Butter?_ What I finally learned is that I am a trained professional. I came to the writing in the same way as I chef my restaurant: I am the final editor. I don’t let plates of food leave the kitchen that aren’t good. I see a plate and think, this looks too burnt, this is over-salted, and I send it back. I used to submit work and hope for the editor to say, "Wow, this is beautiful!" or "Ooh, this is weak." I’m not a child any longer; I don’t need an authority figure to tell me when I’m good or bad. I know when it’s weak and I know when it’s beautiful; I have my objective eye for what’s good and what’s bad and I can use it. Even on myself. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipe]] Food and literature — how does each get at the root of who we are? I don’t know how it’s done with literature, but when someone can get the human experience down accurately and you, alone in your chair, are reading that 200 years away from whoever has written it, and your chromosomes start shaking in your body, this person has spoken the human truth. That is a vital and necessary part of the human existence and we can’t live without it. We also need food in that very elemental way; we can’t live without it. But food for me is a craft, and only a craft. You talk about what you do as a craft, and yet you write with a certain passion about making pasta by hand with your mother-in-law, about the meals you were served when traveling in Europe. So how do you square the two — a workmanlike sensibility and a passionate heart? Are they mutually exclusive? I can have both, can’t I? That sounds just about right. The more I understand about human beings, that is exactly what defines us. We embody simultaneously contradictory positions. p(bio). Florida-based writer Ellen Kanner keeps a website and a blog and contributes regularly to the Huffington Post.

reference-image, l

bookcover, l