reference-image, l

(article, Paul Bertolli)

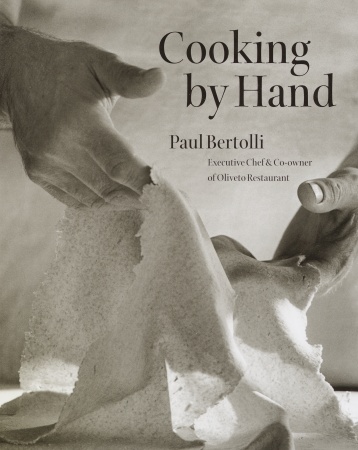

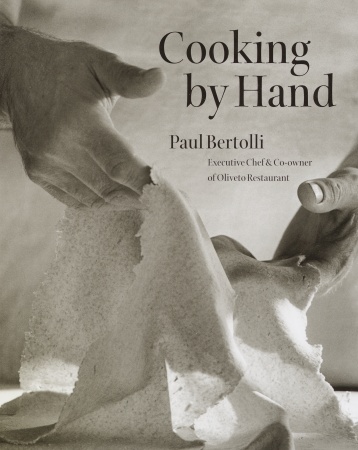

[%adInjectionSettings noInject=true][%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] h3. "Looking at Pears," from the chapter Cleaning the Fresco For six weeks now I have watched various kinds of pears ripen on my kitchen table. Although the apples that sit among them inspire a kind of admiration, pears capture my attention; they appeal to my heart. Pears are more beautiful than handsome. Where the flavor of the apple is robust, the pear is subtle. Bite into an apple and you meet resistance. The pear is soft and yielding. Add to this the exceptionally smooth skin of many varieties, the fairness and occasional blush of its cheek, and the graceful curve of its form. [[block(sidebar). h1. About the book and author The former head chef at Oliveto, a restaurant in Oakland, California, Paul Bertolli is also the founder of Fra' Mani, a salumi business. Dating from his years at Oliveto, Cooking By Hand is Bertolli's lone cookbook so far, a manifesto for appreciating pure whole ingredients and taking care with them, from fresh tomatoes to charcuterie. Copyright © 2003 by Clarkson Potter. Excerpt reproduced with permission. ]] A pear sheds no tear like the fig, to signal its peak, nor is its perfume or suppleness a reliable indication of its readiness to be eaten. In the words of one English epicure, Edward Bunyard, in [%amazonProductLink asin=0812971574 "The Anatomy of Dessert,"] "The pear must be approached, as its feminine nature indicates, with discretion and reverence; it withholds its secrets from the merely hungry." Ripening pears can be frustrating. Patient waiting, sometimes for weeks, often produces no observable change, whereas it is also common to return, after what seems like a matter of hours, to find fruit that has transformed to a musky mess. This behavior on the part of the pear leads to the opinion that it is an inscrutable and uncooperative fruit. This is not an altogether fair assessment. Ripening proceeds at different rates among different varieties of pears. The Winter Nellis doesn't ripen like the Bartlett or the Bosc; nor does the same measure that one uses to judge the progress of one apply to the other. Bartlett ripens much faster, develops a noticeably rich perfume, softens dramatically, and lightens in color. Such transformations in the Winter Nellis and the Bosc are muted and occur more slowly. Senescence follows ripening and is marked by the deterioration of the fruit and the cessation of its functions. Like all living things, the fruit is "mortal," although the seed survives. [%image feature-image float=right width=400 caption="Pears are one of the most ephemeral fruits."] The pear is one of the most ephemeral fruits. Once it has reached its culmination, it makes fast toward decay. But unlike other fruit, it prefers to exhibit no shame and rots from the inside out. The virtue of the pear's subtlety is not without its cost. One must reach for the full flavor of the pear and, as with all subtle things, imperfections are more noticeable. Pears can be profoundly disappointing. When captured at the elusive moment of ripeness, however, a pear is nothing less than a consummation. Planning to enjoy a perfectly luscious pear depends on choosing suitable fruit, the right environment for ripening, and understanding the behavior and particular indications of certain varieties. Generally speaking, the optimum condition for storing pears is a room temperature of about 65 degrees and a relative humidity of 80 to 85 percent (which rules out the refrigerator as an option). Pears ripen when set out in layers in a dark or shaded place. At higher temperatures or in sunny spaces, pears tend to ripen too quickly. Gauging ripeness is a matter of being on the lookout for color shifts, changes in firmness and fragrance, and weight in the hand. While no increase in actual weight accompanies ripening, ripe fruit nevertheless possesses a gravity that must be felt to be understood. Ultimately, it is the act of attending to the course of ripening that matters the most. In this, pears have taught me much about restraint and the rewards of patience. Most of all, I've learned that the art of cooking consists largely of "watching" with all the senses. Fruit "intends" nothing as it relates to human consumption. Its ripening is fundamentally a biological imperative rather than a wish to please human taste. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipe]] Other foods are even more passive in this regard. The flesh of animals or fish couldn't care less. The ripening of cheese runs its own course. Yet all food offers the promise of an answer to human needs and desires, from basic sustenance to aesthetic and sensory pleasure. It is therefore up to us not only to notice food but also to nurture it to this end. To neglect a pear on the table and then return to find it ripe days later is merely a lucky coincidence. But to keep a pear in mind as it ripens is to practice cooking in its simplest form. It is through such observance of any food from the point of purchase throughout its preparation and later in the act of eating itself that cooking is purged of lapses of attention, imposed formula, impatience, or expediency. Like a fresco restored to its former clarity, food reveals what we wish for or remember it to be.

reference-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l

promo-image, l

newsletter-image, l