pollan, l

(article, Twilight Greenaway)

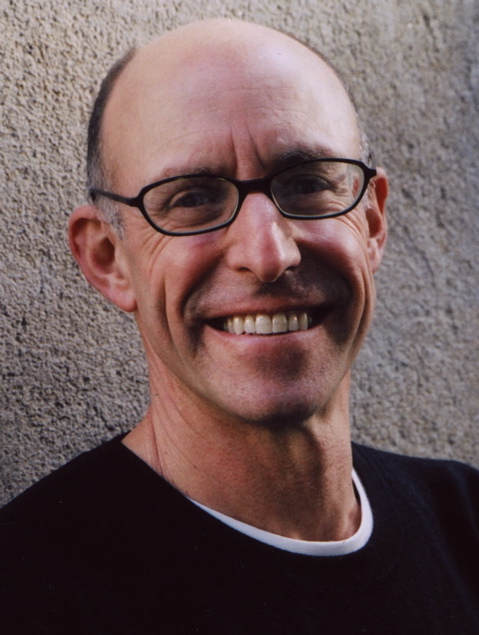

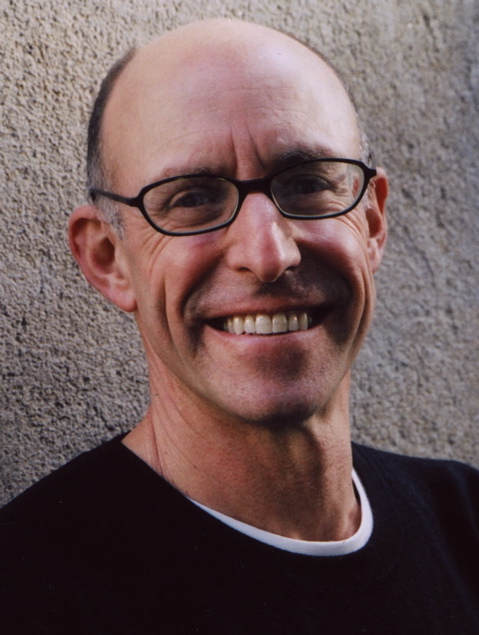

[%pageBreakSettings maxWords=1200] Last week, in the days immediately following the public discussion held February 27 on the UC Berkeley campus between journalist Michael Pollan and Whole Foods founder and CEO John Mackey, the blogosphere lit up with glowing reviews. [[block(sidebar). h1. About the author Twilight Greenaway is a freelance writer based in the Bay Area. Before writing this opinion piece, she wrote for Culinate about locavores and Gary Paul Nabhan. ]] The discussion, hosted by Berkeley’s journalism school, was an extension of an online dialogue between the two men over the last six months. In his bestselling 2006 book The Omnivore's Dilemma, Pollan described his experience of shopping at Whole Foods, where he said he found an abundance of quaint, pastoral storytelling about the origins of the food that didn’t reflect the stores’ increasingly industrial approach to organic food. Mackey objected to the fact that Pollan had not spoken to him directly while doing research for the book, and the two exchanged a series of online letters that can now be read on both Pollan’s and Mackey’s blogs. In the post-discussion blogosphere, Mackey was described as “unpolished and passionate.” He showed an impressive “intelligence and passion for ecologically grown food,” and he was lauded for “generally talking in plain English, and never digressing into corporate speak.” Even here on Culinate, the 53-year-old Mackey was described as “coming out ahead.” [%image pollan float=left width=120 caption="Michael Pollan"] Then again, maybe all these commentators were expecting someone more like Enron's notorious former CEO, Ken Lay. And in truth, for a CEO Mackey is strikingly down-to-earth. He has a sense of humor and isn’t afraid of self-deprecation. He’s comfortable in front of an audience, but doesn't seem unusually slick. Mackey started the evening with a nearly hour-long PowerPoint presentation about the history of agriculture, the failings of industrialization, and the new “ecological era” in agriculture, which he described as “attempting to correct the failings of the industrial era.” [%image mackey float=right width=120 caption="John Mackey"] In more traditional CEO fashion, Mackey also took the opportunity to announce a number of new initiatives at Whole Foods, including new labels for artisanal foods, a $30 million venture-capital fund to sustain artisanal-food producers, and a new in-store fair-trade rating called the Whole Trade Guarantee. What Mackey did not mention was the fact that his grocery-store chain had just grown by nearly 50 percent. Only a few days before the Mackey-Pollan discussion, Whole Foods had announced that it had bought its largest competitor, the Wild Oats chain, adding 110 new stores across the U.S. and Canada. The decision not to mention this significant development was no accident — and after taking a closer look at Mackey’s strategy that night, it comes as no surprise. This 1960s radical turned free-market libertarian knows how to work a crowd, and in front of this particular audience, appearing too large or too corporate would have meant sudden death. [%image omnivore float=left caption="Pollan's bestselling book."] In a room full of dyed-in-the-wool Berkeley liberals, Mackey had the advantage of the underdog, and he made the most of it from the beginning. “How many of you have read Michael’s book?” he asked, watching a predictable sea of arms shoot up. When he followed it with, “How many of you have read my book?” the room grew as still as an old Western flick right before the shootout. But those who had read the written exchanges between the two men may have been disappointed by Pollan’s in-person tone, which was anything but cowboy-like. The author took a far gentler and more diplomatic approach on stage, a tone that made his two letters to Mackey seem nearly demanding by comparison. On the other hand, Mackey’s written approach prepared us for a cultivated ability to make Whole Foods look resilient and, more importantly, already way ahead of any criticism that might come its way. Mackey’s mission, it became clear, was to assure the audience that he (and by proxy, all of Whole Foods) was in complete agreement with Pollan, whose catalyzing book Mackey praised as “genius.” And although many in the audience appeared fidgety as Mackey made them sit through a hefty dose of choir-preaching, they were also surprised to see him show a disturbing (if somewhat stock) animal-rights activism video. [%image wholefoods float=right caption="The Whole Foods logo."] Between the gratuitous shots of paralyzed farm animals and other visual pyrotechnics, however, Mackey inserted a series of subtly antagonistic points that did the double duty of agreeing with the dominant perspective in the room while picking it apart. For instance, although Mackey and his marketing team are carefully positioning themselves as friendly to the local-and-sustainable food movement — they have announced several new initiatives this year, including the addition of actual farmers’ markets in the parking lots of many Whole Foods stores — Mackey also repeatedly characterized Pollan’s views of corporate organics as “exaggerated.” He then spent a great deal of time persuading the audience that, in the case of the environmental impact of buying locally, “fossil-fuel savings have been greatly exaggerated by some advocates.” And for all his talk about increasing the percentage of produce bought locally, only 16 percent of the produce Whole Foods sold last year was sourced locally, while next year that amount is estimated to rise by just four percent. Because the majority of Mackey’s assertions appeared on slides that he moved quickly through without taking questions from the audience, the information he presented came across as pure, unadulterated fact. Much of it, however, was nothing more than spin. In one striking example, a slide repeated a number that Mackey had cited in his written response to Pollan’s second letter: “At Whole Foods, 22 percent of our organic produce comes from large corporations, and 78 percent comes from independent family farms.” In its original online form, that statement read differently (italics are my own): "Of our top 150 suppliers/brokers in the produce category, 22 percent of our purchases are from large corporate farms and 78 percent are from independent and family farms (some of these smaller farms pool together under one brand name to help improve marketing and distribution). Sixty percent of these 150 suppliers grow organically, and/or represent growers who do so." After reading Mackey’s description of Earthbound Farm, the biggest organic produce grower and shipper in the United States with $450 million in sales last year, it becomes clear that what some may consider the most obvious example of “corporate organics” might actually fit in Mackey’s “small farm under the same brand name” category. [%image earthbound float=right caption="The Earthbound Farm logo."] “Earthbound is not quite the large monolithic industrialized organic farm that you portray it as being,” Mackey wrote in the same letter. “Earthbound buys its product from 185 organic farms of varying sizes and consolidates this diverse group of farms together under one brand and one distribution system.” Either way, there’s plenty of gray here. In a May 2006 San Francisco Chronicle article, Earthbound’s Drew Goodman referred to the fact that he sees Earthbound’s size as exactly what allows them to do business with Whole Foods. "Our food system is industrial," Goodman told the Chronicle. "The only way to play that game is to reach the scale that you can get into Kroger's and Whole Foods." Another “fact” presented by Mackey’s presentation was this: “If you live in Berkeley, you will use less fossil fuel and produce less carbon dioxide by buying rice from Bangladesh than from California.” He attributed the statement to the bioethicist Peter Singer (The Way We Eat), who did, in fact, give an interview last year to Mother Jones magazine about the relative fuel use of shipping food by various transportation methods. [%image singer float=left caption="Peter Singer's 2006 book about our food system."] Singer’s statement, however, is clearly put forth as speculation and not fact (once again, the italics are mine): “People often don’t realize that if you’re shipping something like rice by sea, the fuel costs are extremely low ... It may be that if you’re buying rice in California, the rice from Bangladesh has used less fossil fuel than California rice." Mackey is a man of complexity and contradiction. While he talks at length about creating “conscious capitalism,” it is important to note exactly what he means by this. In an opinion piece Mackey wrote for Liberty, a national libertarian journal, he outlined what he sees as his primary political goals: “creating educational choice (i.e, private-school vouchers), privatizing Social Security, deregulating health care, and enacting meaningful tort reform.” Whole Foods is said to treat its employees considerably better than many food retailers, but Mackey has repeatedly blocked his staffers from unionizing and, several years ago, even went so far as to distribute a 19-page summary of his libertarian views, called “Beyond Unions,” to his employees. The memo asserted that, under unions, workers earn lower wages and fewer benefits. When discussing organics — a market many of us were told for years required more demand to bring down prices — Mackey announced, “Until recently, organic (food) was steadily getting cheaper. In the last couple of years that has reversed; now, it’s really hit the mainstream and the demand has skyrocketed.” So, although Whole Foods did a billion dollars’ worth of organic sales in 2006 and is, in Mackey’s words, “largely responsible for the organic supply chain,” that supply chain is still not sufficient to make organics affordable to the average shopper? Looking at these facts side by side, it’s hard not to wonder about the impact that profit margins have on final consumer prices. Is it a coincidence that, simultaneous with these recent price rises, Mackey told Pollan that, after years of having no money (beyond what it took to make an enormous number of shareholders quite wealthy), Whole Foods finally has “enough cash flow to start recycling some of it” into its new micro-loans and social-investment programs? As Pollan put it, “One of the most important things you’ve done is persuade Americans to spend more of their money on food.” Much conventionally produced food, of course, is not priced in a way that reflects the true cost of its production on the environment, the workers who grow it, and the consumers who eat it. But Pollan added, “We spend too little on the whole; however much is profit, I’m not paying attention to that.” When Pollan noted the surprising number of people who had bought tickets to see the evening’s public conversation — which had to be moved from a moderately sized auditorium to Zellerbach Hall, UC Berkeley’s main performance hall — he added, “What we’re witnessing is not just a market, it’s a social-reform movement.” If he’s right, then it’s not a surprise that so many of us are beginning to want to pay farmers and even grocers and distributors a fair price for what we eat. And for many, attention to profit — how much and who benefits — is something to which many of us are actually paying quite a lot of attention. [%image gloves float=right caption="After the bout." credit="Photo: iStockphoto/tacojim"] It's clear that Mackey understands this, and must participate in a dialogue that is critical of the old guard of industrial agriculture in order to secure a place in “the movement.” When Pollan pointed out that the success of Whole Foods can be seen as a “warning sign for industrial agriculture, meaning there’s a growing unease about industrial agriculture on the part of the consumer,” Mackey chimed in, adding, “There’s a strong vested interest in the industrial system,” and “People don’t give up power willingly.” And yet, it is hard to avoid the power that Mackey and Whole Foods represent. Mackey himself described it in Liberty as “the most profitable public food-retailing business in the United States, with the highest net profit percentage, sales growth, and sales per square foot.” Those listening to Pollan’s careful use of language may have picked up on his attention to these contradictions. For instance, when discussing Mackey’s plan to institute a new five-star rating system that will recognize food produced at a higher standard than today’s organic certification allows, Pollan asked, “Is it fair to say your strategy — given the fact that organic is becoming so ordinary in the market — is to find things beyond organic?” Mackey’s response was only that setting the company apart in the marketplace was, in his mind, second to fulfilling their mission, or “deeper reason for being.” In his second letter to Mackey, Pollan had extended a complex, sincere sentiment: bq. I've wondered if perhaps I did, as you imply in your letter, present a unfair caricature of Whole Foods in The Omnivore's Dilemma, suggesting a store where organic, local, and artisanal food is just window-dressing to help sell a much more ordinary industrial product. Indeed, nothing would please me more than to conclude I owe you and the company an apology. I'm not quite there yet. But I sincerely hope you will prove my portrait of Whole Foods wrong, that the company has not thrown its lot in with the industrialization, globalization, and dilution of organic agriculture, but rather stands for something better. For my own part, I stand ready to write that apology, and look forward to doing it. In his response, Mackey had been sure to say that an apology was not what he was after. Yet what he did get from Pollan — the time and space to outline a vision for change and to gloss quite a few of the facts — might seem just as useful in persuading a large portion of his audience that he's on their side. If what we witnessed that night bears out, Pollan may never have real reason to extend that apology. p(bio). [twilight.greenaway@gmail.com "Twilight Greenaway"] is a writer living in the Bay Area.

pollan, l

mackey, l

omnivore, l

wholefoods, l

wildoats, l

earthbound, l

singer, l

gloves, l

reference-image, l