reference-image, l

(article, Christina Eng)

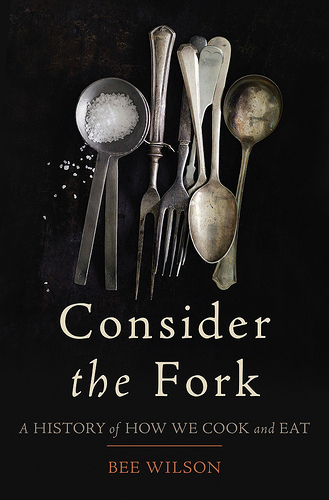

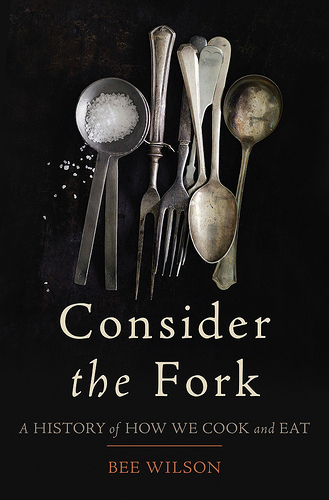

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] In my cabinets, there are chopping boards and mixing bowls, a colander and a salad spinner. My drawers contain wooden spoons, slotted spoons, and spatulas. I have knives, measuring cups, and can openers. There is a bowl I like to use for breakfast, whether I am having cereal or oatmeal or yogurt. There is a mug I like to use for coffee in the late afternoon. And a particular spoon with which I like to stir that coffee. We all have favorite utensils, be they bowls, mugs, or spoons, or pans, pots, and knives. We pick them up often, preferring them to others for certain foods, meals, or cooking techniques. In the well-researched and thoroughly engaging Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat, British food writer Bee Wilson looks at the relationships between the tools we have and the things we make. She explores the ways in which “the implements we use in the kitchen affect what we eat, how we eat, and what we feel about what we eat.” Wilson (Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee) gives us a highly accessible yet comprehensive assessment of the evolution of our cooking habits, tracing, for example, our integration over the years of fire and ice. Once upon a time, she notes, a single fire from an open hearth “served to warm a house, heat water for washing, and cook dinner. For millennia, all cooking was roasting in one form or another. In the developing world, the heat of an open fire remains the way that the very poorest cook.” [%image feature-image float=right width=400 caption="How do the implements we use in the kitchen affect what we eat?"] To work effectively with that fire, we forged “a host of related tools,” including spits, spit-jacks to rotate meat, tongs, pot hooks, drip pans, trivets, and flesh-forks for pulling pieces of meat out of a pot. These usually had long handles and were made of heavy metal. Our currently popular kitchen tools — short-handled stainless-steel tongs or nonstick silicone spatulas, for example — “wouldn’t stand a chance" in that environment, she writes. "The utensils would melt. I would fry. The children would howl. Dinner would burn.” These days, we are able to produce many more heat sources than simple fire. And we can control fire itself more easily. I can adjust the flame on my stovetop with a knob, for instance, turning the temperature up to boil a kettle of water or down to effect a slow braise. Inside our ovens, which, in ancient and medieval Europe, were “vast communal chambers” used to bake bread for entire villages, we make cookies and cakes just for ourselves. We also now have microwave ovens. Invented by Raytheon engineers working originally on military radar systems, they were first sold in the 1950s. They did not hit mainstream markets, however, until about 1967, when manufacturers got the price of a unit down below $500. By the 1980s and 1990s, microwaves had become seemingly indispensable. We use them to reheat leftovers or to avoid food prep altogether, popping in store-bought frozen entrées when we eat alone or cannot cook. What we gain in convenience, however, we lose in connectedness. Like fire, ice matters in the kitchen. “The efficient home refrigerator entirely changed the way food — getting it, cooking it, eating it — fitted into people’s lives," writes Wilson. The refrigerator changed what we ate. Rather than rely on salted meats or preserves because we had to, we could enjoy fresh meat, milk, and green vegetables whenever we wanted to. It also changed how we bought food: “Without refrigeration, there could be no supermarkets, no ‘weekly shopping,’ no stocking up the freezer for emergencies.” And it affected other industries, giving rise to such products as Tupperware, first sold in 1946, and Saran Wrap, introduced in 1953, as well as frozen foods and beverages. Orange-juice concentrate, for example, was the most successful commercially frozen product in post-war America, selling 9 million gallons in 1948-1949. We increased our eating and drinking options. What sets Wilson’s discussion apart from those of her contemporaries, though, is her additional focus on simple hand-held tools. Like Steve Gdula (The Warmest Room in the House: How the Kitchen Became the Heart of the Twentieth-Century American Home), Wilson examines the overall design of our cooking spaces. But much to her credit, she details seemingly ordinary items, too, making her book all the more appealing. She pays significant attention to smaller things, the items we generally don't even think twice about, the odds and ends we have on dish racks or countertops and pick up mindlessly every day. Take, for example, the wooden spoon. It is, at heart, a low-tech gadget. “It does not switch on and off or make funny noises,” Wilson writes. “It has no patent or guarantee. There is nothing futuristic or shiny or clever about it.” Yet it is amazingly versatile. [%image forkcover float=left width=300] Study it. What is it made of? Beech or a denser maple? How is it shaped? Is it oval or round? Cupped or flat? Has it got a pointy part on one edge “to get at the lumpy bits in the corner of the pan”? Is the handle short, for children first learning to cook, perhaps, or longer, for adults to keep splatters at bay? Wood, Wilson reminds us, is a nonabrasive material, gentle on pots and pans. It is nonreactive and won’t leave a metallic taste in food. “It is also a poor conductor of heat, which is why you can stir hot soup with a wooden spoon without burning your hand.” Above all, it is familiar. We cook with wooden spoons because we always have. That our workspaces are mishmashes of old and new tools should not surprise us, Wilson says. On the contrary, eclectic collections reflect our changing personalities. Chopping boards sit alongside food processors. Melon ballers can be popular one year, handheld blenders all the rage another. We don’t necessarily want to reinvent cooking; we only want to make it easier. We learn to adapt and improve our skills over time. In most cases, “whisks, fire, and saucepans still do the job pretty well. All we want is better whisks, better fire, and better saucepans.” Some things we might inherit from parents, grandparents, aunts, or uncles. Some we might receive from friends. Others could be gifts to ourselves. As it is with the utensils in my kitchen. As it is, I suspect, in all our kitchens. The food we make is not only a combination of ingredients, Wilson reminds us: “It is the product of technologies, past and present.” It is a compendium. p(bio). Christina Eng is a writer in Oakland, California, and a frequent contributor to Culinate.

reference-image, l

forkcover, l

featurette-image, l

feature-image, l