reference-image, l

(article, James Berry)

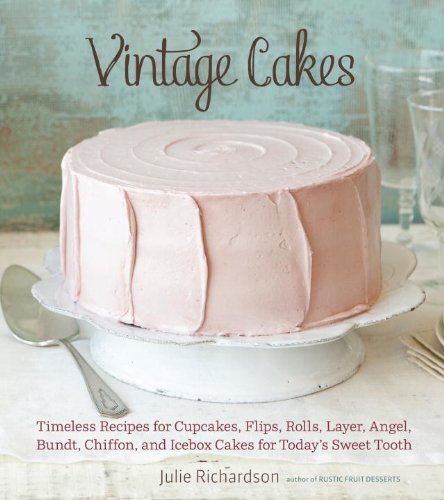

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] Partisanship has taken over the dessert course: Are you a cake person, or a pie person? People seem to feel the need to throw in their forks with one or the other. Honestly, I’ve never understood the need for competition between desserts. Can’t we all be friends, at least at the table? Aren't they all delicious? In my circles, Team Pie seems to have the upper hand. But if you belong to Team Cake, and you want to persuade a pie lover to switch sides, you'll want Julie Richardson’s Vintage Cakes on your cookbook shelf. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipes]] Several years ago, Richardson opened Baker & Spice in the Hillsdale neighborhood of Portland, Oregon. When she moved in, Richardson found a box filled with recipes and paperwork from the previous tenant: the Hillsdale Pastry Shop, which had occupied the space for 50 years. She set the box aside and, busy with running her own bakery, forgot about it for a few years. But neighbors kept requesting the former bakery's Champagne cake, so one day, Richardson dug up the box and began to go through it. The recipes inside were mostly unfamiliar, and they piqued both her curiosity and her taste buds. Intrigued, she began collecting and tinkering with old recipes. Vintage Cakes is the result of her explorations. [%image stackcake float=right width=400 caption="The Stack Cake is a spice cake with a homemade plum filling."] The book's recipes come from many sources: Richardson's family, friends, and neighbors; church and Junior League cookbooks; a Betty Crocker ad; the 1967 issue of Baking Industry. The 1963 Pillsbury Bake-Off winner made the cut. Richardson even delved into 1970s-era cake mixes, and came up with scratch recipes for old favorites. Finally, three cakes — Goober Cake, Double Dip Caramel Cake, and the much-requested Champagne Cake — come from that box of paperwork she set aside on moving-in day. Having the blueprints for cakes that harken back to our childhoods — or our mother’s or even grandmother’s — is like having a time-travel machine. And Richardson’s methodical reworking of the recipes ensures that this Cake Travel will also be delicious. Chapters are devoted to hasty cakes (many of which she suggests we consider eating for breakfast — as if we need encouragement), party cakes, layer cakes, and more. I was particularly happy to see the chapter on flips and rolls, as I firmly believe that jelly rolls deserve a return to the dessert plate. Their hypnotizing swirl belies their easy preparation, and their serving sizes are generally smaller than that of a layer cake (a good thing, if you happen to be watching your dessert intake). Richardson has interesting additions here, from a crowd-friendly German Chocolate Roll to a coffee-crunch spiral (based on the famous Blum's Coffee Crunch Cake). I’m especially intrigued by her butterscotch cream roll-up, a chiffon roll cake filled with butterscotch cream and served with a butterscotch drizzle. Instead of the classic jelly-roll shape, Richardson rolls it into what looks like a huge cinnamon roll, the spiral visible from above; it looks like breakfast served for dessert. That architecture might have been tricky to follow from words alone, but the accompanying photos clarify. The photos throughout the book are stunning; they both tempt and instruct. Richardson’s skills are especially obvious in the hasty-cakes chapter. She rethought these rustic cakes, whose roots go back to the Colonial era, but kept their integrity. The Ozark Pudding Cake, popularized when Bess Truman served it in the White House, was originally made with apples. In Richardson’s hands, it becomes a quick dress-up for two pears and some dried cranberries. The Shoo-Fly Cake retains its molasses flavor, but the batter is lighter than other recipes I’ve seen. Looking to her own childhood favorites, Richardson uses nifty baking skills to turn box-mix favorites, such as the Cherry-Chip and the Watergate Cake (a mix that also called for boxed pistachio pudding; Richardson adds a recipe for that), into cakes a home baker can proudly serve. It would be easy for a book like this to be gimmicky, especially with cakes like the Harvey Wallbanger (does anyone still have a bottle of Galliano liqueur lurking in the liquor cabinet?) and the re-engineered cake mixes. But it's not. Vintage Cakes is a solid cookbook, with technical explanations helpful to novice and expert alike. In the "Tips and Techniques" section, for example, rather than simply instructing the baker to both sift and whisk the dry ingredients, Richardson explains why you need to do both. (Sifting only aerates, while whisking helps evenly distribute salt and baking powder and/or soda throughout the batter, which will help the cake rise properly.) [%image champagnecake float=left width=400 caption="The Champagne Cake was the perfect vintage cake for a 50th birthday."]Similarly, we all know we’re supposed to start out with room-temperature butter, but Richardson goes one step further and explains why: if it’s too warm, you’ll end up with a greasy, dense cake, and if it's too cold, you’ll get poor aeration, which won’t make the fluffy cake of your dreams. And the cakes themselves? I have a long list of cakes yet to try. Topping it is the Honey Bee, made with a honey-enriched batter. The warm-from-the-oven cake gets soaked with a honey-butter glaze and sprinkled with sliced almonds. A second glazing seals the nuts. The Goober Cake, a peanut-butter cake with peanut-butter frosting and chocolate ganache, is just too fun to say no to. I might take Richardson’s suggestion and use jam instead of ganache to fill the peanut-butter cake. Perhaps then I can have a slice for lunch? The cakes that I have tried? They've all come out perfectly. The Kentucky Bourbon is a buttermilk Bundt cake (it won that 1963 Pillsbury Bake-Off contest) with bourbon in the batter and in the soaking glaze that's poured over the cooling cake. The Maple Pecan Chiffon Cake with a brown-butter icing unites most of my favorite flavors. (That icing, incidentally, is made from butter, sugar, and cream. The simple technique of browning the butter adds layers of flavor.) The Champagne Cake's moist layers and custard filling taste like sips of, well, Champagne. Dressed up with a little sprinkling of gold leaf, it was the perfect vintage cake for a vintage (50th) birthday. I’d serve it at any anniversary. [%image cakephoto float=right width=300 caption="The Honey Bee Cake: We tried it and loved it."]My favorite, though, was the Stack Cake. Traditionally flavored with ginger and filled with apples, Richardson’s version is delicately scented with ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves. For the filling, she slowly cooks plums in butter. You could use any plum or pluot; I just used the Italian prune plums from my neighbor’s tree. My finished Stack Cake was a bit lopsided, unlike the photo in the book, but somehow that seems OK with this earthy cake. I served the cake to my book group. One member came up to me after he’d finished his piece. “I’m a pie guy, and don’t usually care for cake," he confessed. "But I think that was the best cake I’ve ever tasted.” He had seconds. p(bio). Giovanna Remolif Zivny is a writer living in Portland, Oregon. Her writing has appeared in Gourmet magazine.

reference-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l

promo-image, l

stackcake, l

cakephoto, l

champagnecake, l

newsletter-image, l