jacques, l

(article, Ellen Kanner)

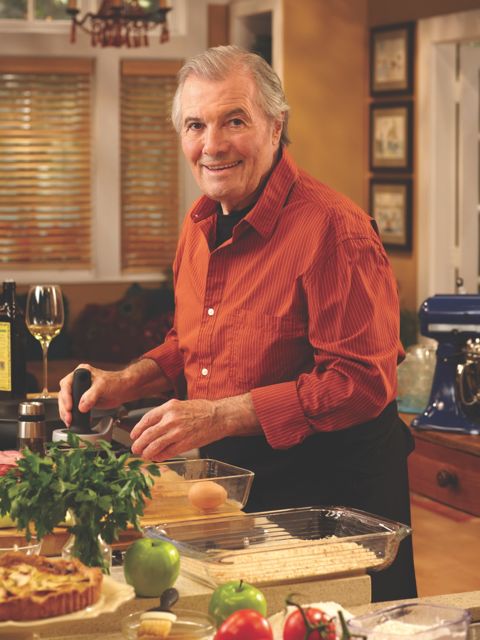

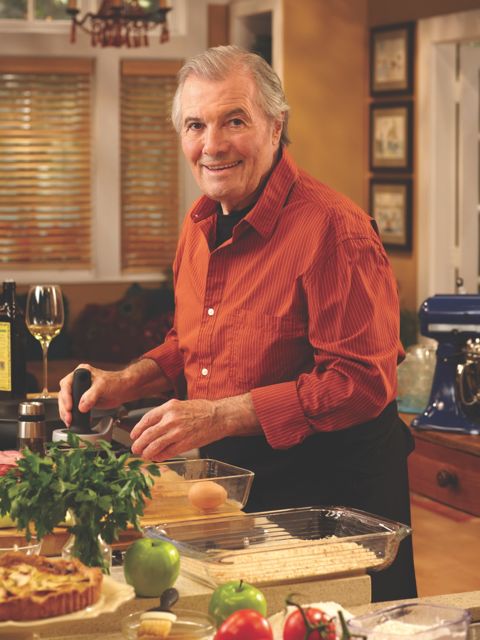

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] p(blue). Before there was the Food Network, there was Jacques Pépin. Over the course of a half-century as a chef and instructor, Pépin has hosted 11 cooking shows on public television, all without a gimmick, excessive hair product, or a signature line such as '"Bam!"' His co-stars include another culinary legend, Julia Child, as well as his daughter Claudine. p(blue). In addition, Pépin has written 26 cookbooks, including his new Essential Pépin, which ties in to a brand-new PBS series, his 12th. He’s received France’s Legion of Honor and a handful of James Beard Awards. No wonder Pépin's book editor Rux Martin calls him The Man. But at 75, Pépin does not care about being a culinary icon. He cares about technique. [%image jacques float=right width=300 caption="Jacques Pépin"] p(blue). Born in Bourg-en-Bresse outside Lyon, France, Jacques Pépin spent his boyhood in the kitchen of his mother’s restaurant. At age 13, he undertook a formal and rigorous culinary apprenticeship at Grand Hôtel de L’Europe. He served as personal chef to Charles de Gaulle and a few other heads of state before crossing the pond to America, where he cooked both haute and low. Pépin cheffed at Le Pavillon, then Manhattan’s premier French restaurant, and developed recipes for that most American of institutions, Howard Johnson’s. p(blue). But whether it’s creating a classic coquilles St. Jacques or frying up clam strips, Pépin has always had a method to make it better. He also has a gift for sharing, as dean at the French Culinary Institute in Manhattan and in books like his 1976 classic La Technique. p(blue). Essential Pépin, his latest work, reflects the wide range of Pépin’s appetites and interests. It includes recipes for classic French baguettes but also for quinoa, plus 700 other dishes (winnowed down from a mere 2,000). However, what makes Essential Pépin essential isn’t the recipes; it’s the accompanying three-hour tutorial DVD, in which Pépin demonstrates the technical basics, from deboning a chicken to scrambling an egg. America’s culinary divas Julia Child and Alice Waters were both transformed by their experiences in France. You went the other way, coming from Bourg-en-Bresse to New York. What excited or at least intrigued you about American cooking? I don’t think I knew any American chefs, except for the black kid who worked at Howard Johnson. All the white kids I knew were Swiss, German, Italian, French, Spanish — not American. By the time I went to Howard Johnson, it was a different world. This is why I wanted to go there. I would learn about marketing and chemistry of food production and American eating habits. Did anything about it scare you? Scare? Not really. When I first came here at the end of 1959, I worked at Le Pavillon, a temple of haute gastronomy. I remember, I was living in town, on 48th Street. I used to spend time on 42nd Street going to the movies, two or three at a time, and then having a hot dog on the street. I was not used to that. Most people come to America because of economic pressure or religious or political pressure. I had a very good job in France; I wanted to see America. It was the golden fleece. I wanted to come here. I didn’t intend to stay. From the first time I was in New York, I loved New York. I never went back. But in a sense, my choice was made on my own taste, not formed by any reason. You haven’t always had the nicest things to say about celebrity chefs. You were a television chef before the Food Network, before there was such a term as "rock-star chef." Do you ever feel like you created a monster? Oh, boy. I didn’t create anything. I don’t know what happened. Thirty years ago, a chef was pretty lowly and uninspired. Now we are genius. Your mother was a chef. What’s the best thing you learned from her? To respect food. That’s why I am miserly in the kitchen. That’s her style of cooking; also that of my two aunts. So much Americans think all the French chefs are male. It is true in certain Michelin types of restaurant, but there are only 20 Michelin stars in France, and over 14,000 restaurants. The real cuisine of the roots and the country is women cooking. This is something Americans don’t realize because of nouvelle cuisine. Paul Bocuse, Michel Guérard — they all came here in the 1970s, and there was a lot of publicity. In the psyche of the American people, this is French cooking, but it is a small part of it, really. You trained in France, but you’ve spent much of your life in America. How has that informed the way you cook? I think there is a mixture there. People will define my cuisine more than I will myself. After 52 years of food in America, I am more American than French, but that being said, I don’t try not to be French. Cooking is always a reflection of climatic conditions. Things grow differently and you cook differently. For me, the great thing is always to cook seasonally and what’s around — it’s always better. It’s always the best in terms of taste, and it’s nutritionally the best and the cheapest also. What goes into creating and developing recipes for you? I don’t really know. I just register in my head and forget. Where did I get that idea? Maybe a magazine or a restaurant or something I hear — a discussion with a chef transforms itself into something else, something changes. I always try to simplify — I’m very Cartesian that way. What’s the difference between creating a recipe and writing one? There’s a big difference — and the difference is freedom. When I think of a recipe, I start with an idea. Then you have ingredients — a chicken — and then cuisine d’opportunité. Scallions and mushrooms — they just happened to be there, which I didn’t intend at the beginning. There is freedom, you do whatever you want, you taste and adjust, and each time, you write it down. You adjust, you lower the heat, you react to the food . . . and end up with a typewritten page. Now I give it to you, that typewritten page. It’s structure, it’s closed in. You have to do it this way. It’s a total reversal. That’s why if you redo the recipe several times, it becomes yours. It’s likely that if you cook a recipe and do it justice and it comes out good, the second time, you’ll take a much faster look at the recipe, you know what it tastes like, what it looks like. By the fourth time, you’ll improve the recipe, with more tomatoes or you don’t like the leeks, and a year later, it has become your recipe. You have put yourself in it, and you don’t know where it comes from. That’s the normal process. And you find freedom again. How did you choose the recipes for this book? What makes them essential? Have you seen the three-hour DVD? That, the techniques, are what is essential. This may be the biggest part of the book. It’s not necessary for the book, but if you learn how to peel asparagus or about boning out a chicken, beating a meringue for a soufflé, you can do any recipe. It is professional. At the French Culinary Institute, it’s repeat, repeat, repeat of those techniques until they become part of yourself, your DNA. You can let it go and forget, but your hands are working. It takes time, but it’s extremely important to become a craftsman first. I know a fair amount of chefs who are good technicians and are relatively lousy cooks. If you haven’t talent like Thomas Keller, what you have in your hands, with techniques, can take you to a higher level. In The Apprentice, you write so beautifully not just about your culinary experience, but about your family and how they influenced you. What about the spiritual or social nourishment of food? This is essential. This is what life is all about — you and your family. Food is so much part of that. The other day, I saw this young couple on television. They’re in their late 30s. They have a kid three, four, five, and they have decided to sit down and eat together, rain or shine — every couple of weeks. It was a momentous decision. What happened to the other 14 days? The kitchen is the most comforting place in the house — the smells, the clanging of the equipment, and the voice of your mother, your father. It remains with you the rest of your life. It’s a natural process; it doesn’t have to be complicated. When Claudine was a year and a half, I held her, she stirred the pot, and she “made” it, so she was going to taste. I don’t remember in any time in our 45 years of marriage when I haven’t sat down in the dining room with my wife. We sit down and eat together every day. That’s why I dedicated the book to her. You’ve written 26 cookbooks and done 11 (soon to be 12) television shows. You’ve been a culinary force of nature for over half a century. What keeps bringing you back to the kitchen? I think someone asked that to Julia. We are lucky in the food world. You are born and, maybe a few hours later, you’re fed. Even if I eat well, five or six hours later, I’m ready to eat again. And I’m ready to cook. So what will you cook for dinner tonight? I have some mashed potato left — mix in some eggs and cheese and do a gratin. Lettuce from the garden, garlic-mustard dressing, and some chicken-liver sauté. Wow. Bon appétit!

jacques, l

reference-image, l