reference-image, l

(article, Edna Lewis)

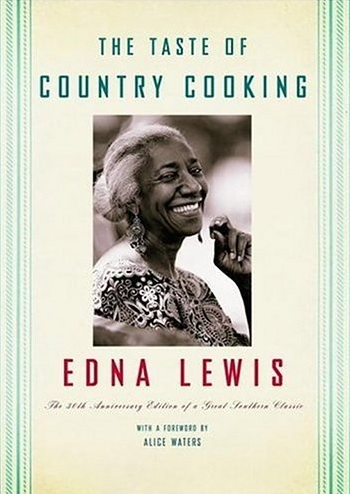

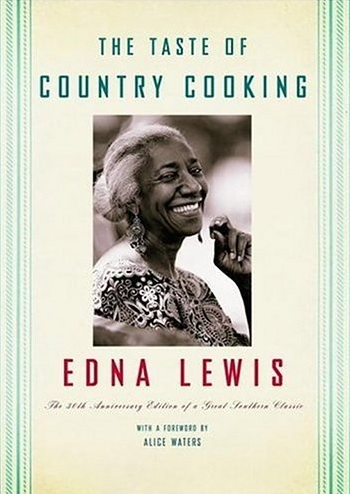

[%adInjectionSettings noInject=true] [%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] h3. From the chapter "Winter" The New Year ushered in long and continued cold weather, the kind needed for developing thick ice on the ponds and rivers. When it reached the desired thickness, the men of Freetown would go out and help cut it into 3- to 4-foot pieces, about 2 to 3 feet thick, and then haul it in. The icehouse was a deep, round cellar about 20 to 30 feet deep, with a roof and door, lined with poles and filled with a good layer of straw with a strong ladder extending down into it. The ice was placed in this cellar and covered with more straw. [[block(sidebar). h1. About the book and author Edna Lewis (1916-2006) grew up in Freetown, a small rural community in Virginia founded by freed slaves (including her grandfather). Lewis grew up cooking with the seasons on a wood-fired stove. After running a Manhattan restaurant for several years, she began teaching cooking classes and writing cookbooks, helping to preserve the recipes and traditions of a Southern way of life and cooking that was disappearing. The Taste of Country Cooking, one of her later books, is both memoir and cookbook, organized by the four seasons and chronicling the food cycles of Freetown in the first half of the 20th century. Excerpt reprinted with permission of Knopf (2006). ]] Once filled, it was left alone until needed on hot summer days. Most farmers had their own icehouses, but we got ours from the icehouse at Lahore. We used it for making ice cream, lemonade, cooling the milk, and sometimes drinking water. It was a great treat to bring the ice home in a burlap bag, chipping off small pieces to eat on a hot day. After the icehouse was all filled up, most activity ceased except for morning and evening feeding, milking, and bringing in water and firewood. It was in between these daily chores that the people of Freetown found more time for visiting each other. There were visitors from nearby communities, especially to visit with Grandpa. A person of his age group (80 years and older) would arrive on horseback or in a buggy, unbridle his horse, and put it in the barn with ours. Then he would visit us for a week or two or three. We liked having visitors. It gave the house a festive air and neighbors would drop by to greet the guest. We children were able to be alone in the next room and relax our behavior without being noticed. A great fire would be going in the fireplace, and we would serve homemade cake and homemade wines that seemed to have been made for just such occasions. There would be lively conversations, with the aged men doing most of the talking and the young adults of my father's age group listening. I would be listening, too, hanging between my father's knees and watching the logs burning in the fireplace and bugs desperately trying to escape from the burning logs with only me being aware of their desperate plight. I was too young then to understand why so much time was spent in discussion. It was only afterward that I realized they were still awed by the experience of chattel slavery 50 years ago, and of having become freedmen. It was something that they never tired of talking about. It gave birth to a song I often heard them sing, "My Soul Look Back and Wonder How I Got Over." While the very intense discussion went on inside, snow blanketed the earth outside. The mood was right for a pot of stew cooking on the side of the fireplace, and some ash cakes, which were made of fresh-ground cornmeal, salt, and water — just enough to make a fairly stiff dough. The cakes were then molded by hand into an 8-by-4-inch egg-shaped pone, wrapped in cabbage leaves, or left unwrapped and put into a clean bed of ashes in the fireplace and left to cook until needed. The summer kitchen had been closed and most of the cooking was done now in the fire hearth. [%image promo-image float=right width=400 credit="Photo: iStockphoto/YinYang" caption="Persimmons, one of the last fresh treats of fall and winter."] The main meal was served in the evening because of the short daylight hours of winter and the early feeding of the stock. This was the time to draw upon the canned vegetables and fruits that had been prepared during those unbearable hot days of the past summer. In addition, there was sausage, liver pudding, spareribs, wild game from the hunting parties, and wild watercress. No winter meal was complete without a fat, old Barred Rock hen saved for a cold day, stewed and served piping hot with dumplings made of a rich biscuit dough. The most popular fresh vegetable was the wild watercress that was gathered from the lowlands just before or after a snow. This was said to be a fine source of iron, good to eat during the dark, gray days of winter, served with baked tomatoes, boiled shoulder, and mashed potatoes. We also had thick soups of homegrown dried beans with slices of pork and hot, crusty breads. And for dessert there would be bread puddings, deep-dish pies, and compotes of canned fruit. Aside from entertaining, there was a great interest in the new seed catalogues that began to arrive after the first of the year. The highly colored pages of seed catalogues were very tempting, although for the most part we used our own seed year after year. (They were not hybrid in those days.) My mother would often be tempted to buy new kinds of vegetables. The seeds were easy to grow and as soon as something was ready to pick we had to cook it and see what that new vegetable tasted like. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipes]] The winter vegetables would consist of some root crops that could be left in the ground all winter and gathered as needed, such as turnips, parsnips, tube artichokes, and salsify with its flavor of oyster bisque — a refreshing change from potatoes in late winter — cabbage, canned corn, and beans. No canned fruit had the fragrance of canned pears. Canned blackberries and peaches were also favorites of ours. So was canned applesauce made into two-crust pies. And a treat was a bowl of clean snow flavored with vanilla and with sweetened heavy cream folded into it, which we called Snow Cream. There were also the perennial dried apples for making dried-apple pie, and dried peaches to chew on. Winter must have seemed forever for our mother, a lover of the outdoors. Along in February she would save all of the eggshells, line them up on the windowsill, place the seed of a green bean in each one, and add about a tablespoon of water. When sprouted enough she would set them, still in the shells, into a prepared row and cover them with soil on the first warm day of spring.

reference-image, l

promo-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l