moldy, l

(article, Jonathan Bloom)

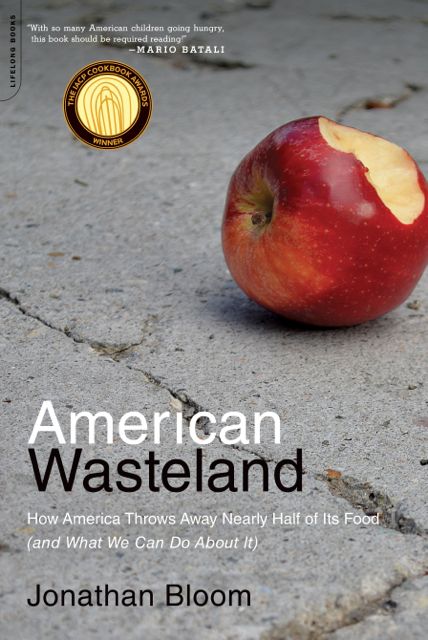

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true][%adInjectionSettings noInject=true] h3. From the chapter titled "Culture of Waste: Our Fall from Thrift and Our Imminent Return" In 1995, after being quoted on the depressing use of land at a middle school in her neighborhood in Berkeley, California, Alice Waters received an offer from that school’s principal: Help us change its culture. And so Waters, the chef and owner of Chez Panisse, agreed to assist the school with what she knew — food. And that’s how Martin Luther King, Jr., Middle School came to have a lush, one-acre garden that nourishes both its students and its curriculum, and the Edible Schoolyard program came to be. [[block(sidebar). h1. About the book and author Published in 2010, American Wasteland looks at how and why almost half of the food produced in the United States goes uneaten. A paperback version of the book is just out. A writer based in North Carolina, Jonathan Bloom is a food-waste expert who writes the blog Wasted Food. Reprinted by arrangement with Da Capo Lifelong, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2011. ]] Waters argues that the reason students often don’t enjoy vegetables and other fresh foods is that they feel no connection to them. Yet gardening and cooking reconnect kids to what they eat and, in so doing, makes them waste less. Their lunches come from items that they cultivated and prepared themselves; they’re not mysterious commodities. “When children grow food and cook it, they eat it, all of it,” said Waters. “And they like to be in the kitchen and at the table. It’s a ritual that is in everyone’s genes. It’s just part of us. We’ve been disconnected from it, but as soon as we get back to the kitchen, we get reconnected very quickly.” This holds true for adults, too. We are much less likely to waste food we prepared ourselves, or that we know our loved one did, than we are to squander something we grabbed from the deli counter at the supermarket. As Waters put it, in universal terms: “You are less likely to waste the food that you know where it came from.” Reestablishing that connection would go a long way toward countering this statistic: The two most commonly wasted school-lunch foods in the 1996 report were cooked and raw vegetables. The study found that an astounding 42 percent of cooked veggies were wasted. That could be partly because canned or frozen vegetables dominate over fresh ones in schools. As a result, lunch ladies and men must contend with the dreaded mushiness factor. [%image moldy float=right width=400 caption="Cheese gone bad."] Increasingly, children don’t even recognize “real” or “whole” foods. They can’t identify the plant, tree, or bush that produced what’s on their plates. How can they, when they’re so unaware of their food’s origins? For the Mississippi students I sat with in Quitman County, being so far removed from the food chain is ironic, because they inhabit some of the most fertile land on the planet. Yet what’s planted isn’t food; it’s a source of income. Cotton fills the fields that mingle with their towns, with soybeans as the other crop. And with fewer folks having backyard vegetable gardens or livestock, most of these children don’t think of food as something grown or raised. That’s a far cry from Joe Ann McDonald’s day. She remembers gathering eggs, raising hogs, and pumping water for the mules, sometimes at the expense of going to school. Our separation from the sources of our food is by no means specific to Mississippi, to children, or to Mississippi children. Over the past century, Americans have experienced a continued physical, intellectual, and psychological distancing from farms. For many children — and plenty of adults — food does not come from the ground; it arrives magically in bright frozen packages, from a delivery man’s car, or on polystyrene trays. Fewer, larger farms now produce our food. And despite our growing population, the number of farms in the United States shrunk by 70 percent from 1935 to 1997. The average acreage more than tripled over that same period. Not only are we not growing our own food, we’re farther away from those who are. That distance from the production of crops and raising of livestock hinders our food knowledge. At the same time, a main driver of urbanization is that fewer Americans are farming, mostly because they’ve been priced out by larger operations. That shift in geography and occupations has both occurred parallel to and aided our transformation from a culture of thrift to one of waste. In her 2007 book [%amazonProductLink asin=0553804952 "Little Heathens"],_ Mildred Armstrong Kalish wrote about growing up on an Iowa farm during the 1930s. At one point, she described cleaning a severed hog’s head to make head cheese. Using a toothbrush, she removed all the dirt from its teeth. Kalish and her siblings used baking soda to clean the grime from its ears and lips. Fortunately for them, the adults had already scraped off the hog’s hair. Looking back on the chore, Kalish wondered, “Can you see a five- to 10-year-old child of today turning to such a task?” Can you even imagine an adult doing it today? True, this is an extreme example of using the entire animal. And yes, it occurred on a farm during the Depression. Yet our day-to-day food experience has changed so drastically that it is unrecognizable to the Americans who toiled on the land just a few generations ago. Cleaning a pig’s decapitated head has almost nothing in common with pushing the start button on the microwave to heat a package of Pigs in a Blanket. Even less shocking tasks from “back in the day” are almost never done at home these days. For example, when was the last time you shelled walnuts or made your own breadcrumbs?

moldy, l

reference-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l

newsletter-image, l

promo-image, l