reference-image, l

(article, Tom Hudgens)

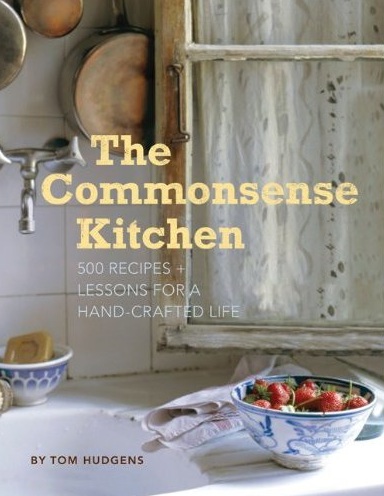

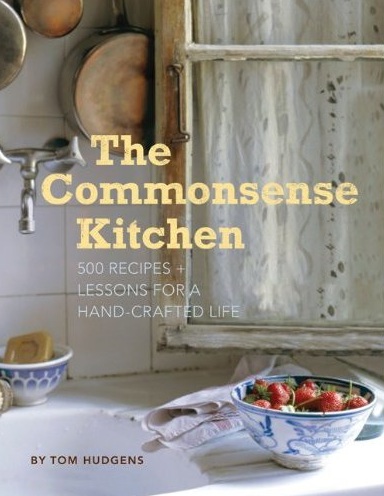

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true][%adInjectionSettings noInject=true] h3. From the section titled "Learning to Cook" [[block(sidebar). h1. About the book and author The Commonsense Kitchen is a plainspoken cookbook from an unusual source: the kitchen of California's untraditional Deep Springs College, a school for young men on a high-desert ranch combining intellectual study with farm work. Tom Hudgens learned to cook as a Deep Springs student. He cooked professionally at several restaurants (including Chez Panisse) before returning as the college cook. The Commonsense Kitchen is a recipe collection developed during his years as the Deep Springs chef. Reprinted with permission from Chronicle Books (2010). ]] Learning to cook is a lifelong process. Every time I mix a batter, slice an onion or peel an apple, I'm learning to cook, provided I'm paying attention. You want to learn to cook? Go into the kitchen and start cooking. Keep cooking. Let your hunger and appetite guide you; cook what you want to eat. Pay close attention to every step in the process, and to your results. Food is our primary, fundamental connection to nature. Even urban dwellers who rarely see the sun or set foot on soil must still eat food grown in the sun, in soil. What is the most highly processed food you can think of? Whatever it is, it is still ultimately based on plants, grown in a field somewhere under the sun. Cooks perform a kind of alchemy, transforming natural products — plants, animals, water, salt — into food that builds and nourishes the body and soul. I believe the dawn of human civilization occurred not at the moment of killing and butchering an animal, but rather at the moment we learned to carefully cook bits of that animal's flesh over the fire without burning it, to brown, smoky, juicy perfection. Learning to cook, like learning any craft or skill, is a matter of learning to pay attention, to ask questions. The best first step in learning to cook is developing close attention to what you eat. What tastes good to you? Why? What we eat affects not only our bodies, but ultimately the whole, interconnected world. To open a can of green beans creates a different result, both in your body and in the world, than if you bought and cooked a handful of fresh green beans. Each choice, no matter how small, makes a difference. [%image feature-image float=right width=400 caption="Aunt Lela's Buttermilk Pie"] Appreciate your food before eating it. Take a moment to be aware of the colors and aromas. Be aware of all the people who worked to produce the food. Use whatever has been made available to enhance your experience of eating. Sprinkle a little salt, if it makes the food taste better. Pepper. Condiments. Squeeze the lemon or lime. Help yourself to any sauce the cook has provided. Spread a little butter on your bread. Be aware of how the different foods offered complement one another. Relish every bite. Lick your fingers. Stop when you're full. Compliment the cook. Pay attention to your food likes and dislikes. With time, they may change. Foods I once hated I now love. When I was a kid, each summer my mother would implore me to taste just one cherry tomato she had grown in our New Mexico back yard: "Just try it," she'd say, "they're as sweet as candy!" I'd dutifully pop one in my mouth, bite into it . . . and gag. Now, as an adult, I love tomatoes of every size, stripe, and hue. [[block(sidebar). h1. Featured recipes]] A friend once insisted on his dislike for cherry tomatoes — until he tasted them simply cut in half with a knife, and then he loved them. He didn't like the way the little tomatoes squirt their juice when they are bitten whole. Halved, their good flavor was more accessible. "I never knew anything so simple could make such a difference," he said. Welcome to the craft of cooking.

reference-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l

promo-image, l