family, l

(article, Emily Puro)

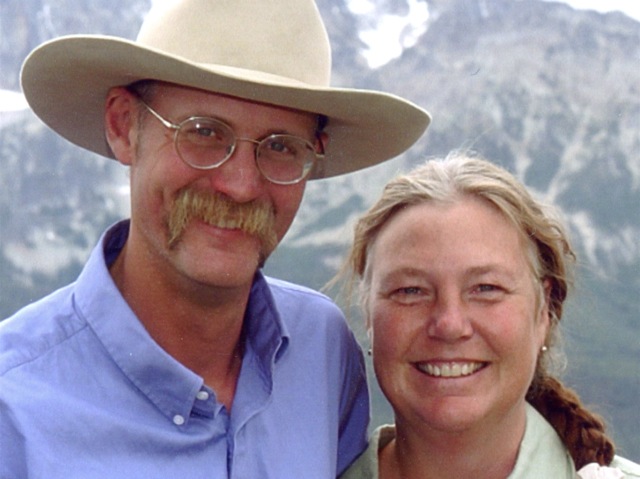

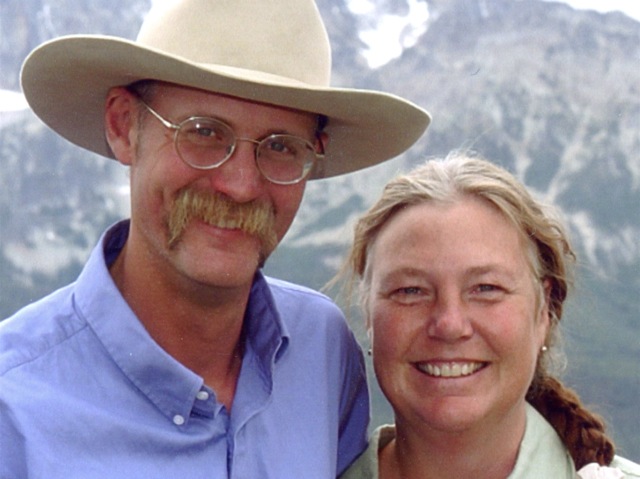

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true][%adInjectionSettings noInject=true] p(blue). On Alderspring Ranch in May, Idaho, Glenn and Caryl Elzinga raise cattle — organic and grass-fed — along with seven daughters, ages 2 to 13. With backgrounds in forestry (Glenn) and plant ecology (Caryl), the Elzingas practice a holistic approach to animal and land management. Why did you go into ranching? Glenn: We were living in the Lemhi Valley in Salmon, Idaho, and we wanted to have a family. And I thought, what better place to have a family than on a ranch with cattle and animals around? Caryl was brought up on a farm in the Midwest, and I had many relatives who were dairy farmers. We both liked the idea of open space, of working on the land. We both love animals. I was traveling more and more in my work as a forester, and we just said, “Hey, let’s do something that’s going to keep us home.” It’s kind of an idealistic view that got us into it. The cold hard reality of night calving at 25 below zero never really occurred to us until we actually started doing it. [%image promo-image float=right width=400 caption="Glenn Elzinga offering grass to the cattle on his ranch." credit="Photo courtesy Glenn and Caryl Elzinga"] What prompted you to focus on grass-fed beef? Glenn: When we started ranching, we were just part of the commercial commodity cattle business. We’d raise the calves all summer and work very intimately with them, and then in October we’d load them up on a truck and they were gone to a distant feedlot in Kansas or Nebraska, and that was the end of it. It was kind of weird. One year we drove through Kansas and Nebraska, and we saw hundreds of thousands of cattle in these feedlots up to their bellies in mud. The smell was incredible, and I just looked at Caryl and Caryl looked at me and we said, “We’re never going to do that again.” We didn’t feel it was right. We raise \[our cattle\] on pastures. It’s basically an open-range situation for them. They drink at a stream. They eat green grass. They’re out there with wildlife. Maybe it’s anthropomorphic, but it’s a good life for these animals here. Another part of it is, every year we kept about five head back for ourselves and our friends, and we tried grain finishing and a little bit of grass finishing. It turned out we preferred the grass finishing, although we found it inconsistent. We started tweaking the grass-fed thing and finally started getting pretty good stuff, and we gained a number of local customers for our grass-fed beef. At the same time, we started noticing more and more interest in grass-fed beef. So you’ve got three things going on: One, Glenn and Caryl are disgusted with feedlot agriculture. Two, we think grass-fed beef is cool because personally we’re starting to like it more than corn-fed beef. And three, it looks like there’s this shift in the public’s eyes toward more of a grass-fed type of animal agriculture. So with those three things kind of lining up at the same time, we said, “It's time to jump through the window and stop selling any of our calves to the feedlot. We're going to raise them all 100 percent grass-fed to sell directly to the customer.” You have to realize it was a gamble. We had to keep the calves for another six to 12 months and bank on the fact that we were going to be able to sell them and recoup the expenses. But the following spring, as we started selling at farmers' markets, this guy named Michael Pollan published a story in the New York Times Magazine called “Power Steer,” and it raised public awareness a great deal about conventional feedlot agriculture and giant beef processing plants. We sold out. How have your backgrounds in environmental sciences influenced your ranching practices? Caryl: I’m fascinated by the use of animals to meet ecological objectives. As organic producers, we’re always looking for ways to change what our pastures look like in a positive way, and there are ways to do that with grazing animals. [%image family float=left width=425 caption="The Elzinga family." credit="Photo courtesy Glenn and Caryl Elzinga"] Glenn: It’s given us a more holistic outlook on how it all works, instead of just looking at this business of "Let’s get pounds on cattle fast and get them out of here." In addition to the nutritional benefits and more humane animal care, what do you think are the biggest advantages of grass feeding? Caryl: Raising animals on a permanent pasture, where the grass stays on the ground rather than tilling up the soil annually to plant a grain crop, is much better for the microflora of the soil. \[We're\] building soil rather than losing soil, keeping soil where it belongs instead of having it erode away into our streams and lakes. Glenn: It goes all the way from improving soils and earthworm density and overall pasture health and supporting local agriculture and local families to reducing sedimentation in the Gulf of Mexico and reducing imported oil use. It’s just this wonderful thing that has the potential to solve myriad problems. What are your daughters’ favorite jobs on the ranch? Glenn: The horseback thing is their favorite. We sort cattle on horseback and we trail them a total of about 20 miles in the fall. It takes two or three days. They like that. Caryl: Right now, all four of the oldest kids have bottle calves to feed. Every morning they mix up the milk and feed the bottle calves, and they do it again at night. They sometimes argue about whose turn it is, but I think we’ve got the kinks worked out with that. It sounds like raising a family was a big part of your decision to start ranching. What do you hope your girls will get out of being raised on a ranch? Glenn: It was probably the biggest reason we got into it. I guess I hope they get a work ethic. I would like them to feel self-assured, because a lot of times they do stuff that’s kind of a grown-up job. Like the 12- and 13-year-olds, I’ll say, “Go saddle up and get those cattle and bring them home,” and they’ll do it. A lot of grownups couldn’t do that. They get a real sense of self-worth. The relationship with animals — I’m not sure what that instills in them, but I think it instills something valuable. They’ve got to go beyond themselves all the time to take care of these animals. I’m hoping that moves into their adult lives where they’ll be able to think beyond themselves into other peoples’ needs. p(bio). Emily Puro is a writer based in Portland, Oregon. Also on Culinate: An article about standing in a farmer’s boots.

family, l

promo-image, l

reference-image, l

featurette-image, l