promo-image, l

(article, Augusta Scattergood)

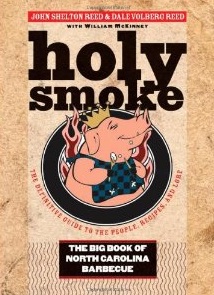

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true] Some foods have imprinted themselves so strongly onto our psyches that the slightest aroma can be transporting. Fresh blueberry pie, for example, can summon up memories of Little League games, beach days, and Grandma’s kitchen table. Nothing, however, speaks to me quite so strongly as barbecue. I spent my formative, food-inquisitive years 111 miles south of Memphis. Even today, when I visit that barbecue capital, if I don’t have time to sit down for a round of the famous ribs at the Rendezvous Restaurant, I’ll drive through Corky’s or stop by Neely’s Bar-B-Que. My order doesn’t change: a pulled-pork sandwich slathered with extra sauce and topped with coleslaw. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipes]] So I have my barbecue preferences — and they aren’t the vinegary flavors associated with North Carolina-style barbecue. Like most stalwarts on my side of the barbecue fence, I stand firm in defense of Memphis' sweet, tangy sauce. However, after reading Holy Smoke: The Big Book of North Carolina Barbecue, I may consider climbing over that fence for a bite or two. According to John Shelton Reed and Dale Volberg Reed, who co-wrote the book with William McKinney, their state’s ‘cue is pork, slow-cooked over hardwood coals, just like the Memphis tradition I know and love. So far, so good. But North Carolina barbecue is distinguished by what the 'cue masters mop on the meat after cooking, or drizzle over it just before eating. And that’s where their traditions and mine part ways. [%image promo-image float=right width=400 credit="Photo courtesy abbyladybug/Flickr" caption="A sample of North Carolina barbecue and sides."] Barbecue is revered across the South, but sauces are always the subject of intense debate. In addition to the Memphis and Carolina styles, there are also the Kansas City and Texas versions — and that's not counting hotly disputed variations, such as the serious dividing line between the two North Carolina schools of preparation. The eastern part of the state prefers vinegar, salt and pepper, and perhaps a dash or so of hot sauce. The Piedmont style favored in the western end of the state adds a little ketchup to the sauce. Both sides agree on one thing, though: Barbecue without coleslaw is not truly authentic. Or, as Wilber Shirley, one of the many cooks and restaurant owners quoted in the book, insists, “You gotta have coleslaw. I won’t even sell somebody a barbecue unless they get coleslaw . . . It all goes together.” Although barbecue mostly needs to be slow-cooked over a hardwood open pit somewhere with a drive-up window or a banging screen door with holes in it big enough to let the flies in, some brave souls smoke their own. Most Southern cooks don’t attempt it in an oven, as the smoky flavor is impossible to duplicate. But if you’re feeling adventurous, Holy Smoke offers detailed directions for building an outdoor pit, complete with the type of fuel to use and, of course, cooking instructions. If you don't feel like building your own pit, and a huge smoker isn’t lurking behind your garage, the Reeds lay out a foolproof way to find the perfect barbecue joint: “It’s almost a cliché . . . that a mix of pickup trucks and expensive imports in the parking lot is a good sign. If the sheriff’s car is there, hit your brakes immediately.” In addition, there should be a woodpile nearby, and you should check it for recent use; if spiderwebs cover the wood, move on. The writers offer tips on evaluating the décor (be sure the old signs are authentic, not of recent Antique Mall variety). And they reassure potential diners that paper napkins and plastic utensils are not only acceptable but de rigueur. After all, the point of a good barbecue place is the food, pure and simple. Holy Smoke introduces readers to a bevy of barbecue aficionados. From Ayden to Shelby, each town has its special men and women who smoke pork, tweak recipes, start franchises — and have done so for generations. That passing-along of recipes and techniques may be the one thing all serious barbecue cooks have in common. Recipes in the book come from eateries all over the state, including the Piccadilly Cafeteria, Mama Dips Country Kitchen, and Crook’s Corner. From cornbread, corn sticks, and hush puppies to collards, okra, and baked beans, plus an entire chapter on desserts, there just isn’t much the Reeds have left out. Maybe those folks who claim their vinegar sauce is better than my sweet tomato sauce have a point, however small. At least the next time I’m driving through the Carolinas and I stop at a joint with a woodpile out back and smoke curling from the chimney, I’ll not turn my nose up at their sauces. And I won't forget to order the coleslaw. p(bio). Augusta Scattergood blogs about food and books.

promo-image, l

reference-image, l