burner, l

(article, Erin Ergenbright)

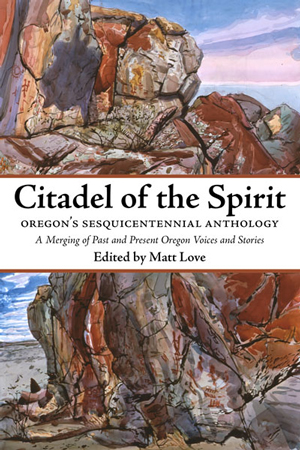

[%pageBreakSettings maxWords=1100] h3. From the essay "The Hands That Feed You" Triumphantly swinging a machete through the waist-high grass, Michael Hebberoy seemed to imagine himself an explorer in dangerous and uncharted territory. It was a bright Saturday morning in February 2005, and, fortified with grappa-laced coffee, we were learning to prune pinot noir vines at Cameron Winery, 30 miles south of Portland, Oregon. We were part of “The Program,” an educational work-study developed by Michael and Naomi Hebberoy, the owners of Ripe, an umbrella organization that sheltered their three restaurants — Family Supper, clarklewis, and Gotham Building Tavern. [[block(sidebar). h1. About the book and author Edited by publisher Matt Love, Citadel of the Spirit is an anthology of original essays and reprinted excerpts about Oregon over the years. The book was published early in 2009 to commemorate Oregon's 150th birthday. Portland writer Erin Ergenbright's "The Hands That Feed You" is a look back at the origins of Oregon's diverse artisanal-food world, culminating in the rise and fall of the Ripe restaurant empire. Excerpt reprinted with permission of Nestucca Spit Press (2009). ]] “The Program” was meant to give us, Ripe employees, a deeper connection to the fine food we served and prepared. And in developing relationships with the farmers who grew the frisée and butter lettuce and asparagus we served, and walking on their land, seeing their chicken coops and turkey pens, made the web of interconnection tangible, and made “sustainability” (essentially the philosophical matrix behind “The Program”) something more than an overused word. The winter sunlight illuminated the low valley beyond the vineyard as we huddled around John Paul, the winemaker and owner of Cameron, watching and listening. Pruning is done after the coldest part of winter has passed; it forces the sap back into the center of the vine, and determines the shape and yield of the plant for years to come. Every year, on every vine, you cut away everything except two fruit canes and two spurs — the ones that seem strongest. The canes grow along wires strung horizontally and produce many offshoots and many grapes. The spurs, snipped above the second buds, will be next year’s canes. “If you make good choices, next year’s choice will be easy,” explained John Paul. He was the only one holding the clippers, which was a relief, as these were 100-year-old vines, and their roots reached deeper than 20 feet into the soil. Paul is a founding member of the Deep Roots Coalition, a group of Willamette Valley winemakers who practice the sustainable, Old World technique of dry farming, rather than using drip irrigation. Through dry farming, vines can find water even in arid climates and through rocky soil, which affects their terroir — the total natural environment of a vineyard, including the geology of the soil, the topography, the climate, and the sunlight. Every bottle of wine contains its history, but we often drink it without a sense of where it came from, or of the specific people and processes involved. Similarly, most of us eat our steaks and fried chicken and sausages without thinking of the animal that lived and died, let alone the person who raised that animal and trucked it to the slaughterhouse, or the person who put a bolt into its brain. The first time I saw our chef use a hacksaw to remove the head of a huge, hairless pig, I had just taken a bite of a pork sandwich, and, though I felt a little queasy, made myself keep chewing, keep watching. Of course I’d known pork and ham and bacon came from a pig, but now I knew it in a visceral way, and would never again be able to think about the meat without the animal. Ripe started in 2001 as a small, underground, and possibly illegal dinner series in Naomi Pomeroy and Michael Hebb’s northeast Portland rental. Bringing together strangers from various backgrounds, the DIY dinners literally embodied gastronomy — the study of the relationship between food and culture, which encompasses everything from art to science to economics and history. A sort of culinary pyramid scheme, wherein you could only attend after being invited by someone who’d already been, Family Supper captured Portland’s imagination, and fed its belief in itself as a city on the verge of cultural relevance. Ripe’s email list eventually ballooned to 15,000, and its near-nightly dinners filled months in advance. [%image "john paul" float=left width=400 caption="John Paul leads Ripe employees on a tour of Cameron vineyards in 2005."] My first Family Supper was New Year’s Eve 2002. My date and I ate a simple, fabulous meal, served family-style — bowls of salad and pasta and platters of meat passed down long tables — with 50 people we’d just met in an industrial kitchen tucked off an unmarked alley in north Portland. The room throbbed with laughter and music and the flicker of votive candles, and near midnight, Michael climbed up on the table, his shoes near my wineglass, and gave a soaring toast. He reminded me of an evangelist preacher at a tent revival. I don’t remember what he said, only what I felt in listening: an overwhelming hope for our future, and that we were part of something groundbreaking, something incredibly important. The beginning of a movement, perhaps, like Paris in the 1920s, San Francisco in the 1950s, or Seattle in the early 1990s. This is it, I thought, as the clock struck 12. I started working with the company a few months later. In January 2004, the couple opened a new restaurant, clarklewis, with chef Morgan Brownlow. Clarklewis received the Oregonian’s Restaurant of the Year award within a few months of opening, which fed the already fierce media frenzy. A year later, buoyed by a staggering amount of local and national press, the couple, now married and known as the Hebberoys, opened Gotham Building Tavern to immediate recognition. But these three restaurants were only the tip of the iceberg. Michael’s other projects included producing a line of Gotham Building Tavern gin to be launched in New York; partnering with the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) to bring Family Supper to New York, Las Vegas, and Tokyo; writing a book entitled Kill the Restaurant: A Manifesto; and hosting Portland author Matthew Stadler as Ripe’s “writer-in-residence.” Indeed, Ripe seemed the center of the zeitgeist that had put Portland on the map. In 2006, Food & Wine ran an eight-page article about the Ripe empire, in which they called Michael a “food provocateur,” and in which he took a risky potshot at Alice Waters, the revered founder of Berkeley’s Chez Panisse, saying, “People say \[she\] launched a food revolution, but they’re wrong. That was only an ingredients shift.” But the Hebberoys' meteoric rise was only made possible by 40 years of priming by a group of visionary chefs, farmers, ranchers, and winemakers in Oregon. Michael Hebberoy spoke of Ripe as revolutionary, when it was, in fact, evolutionary, incorporating their theories and practices, and applying his own uncanny ability to generate press and hype. His ideas weren’t new, but he could talk about them in a way that made them seem groundbreaking, exciting, and important. In the mid-1970s, before the word “sustainability” was coined and became so ubiquitous as to be nearly meaningless, this group of Oregon producers and politicians realized they lived in something like paradise — in close proximity to fertile land, two watersheds, the ocean, and high plains — and made choices to protect them, thus ensuring the area’s future. These choices have produced exceptional local farms, vineyards, restaurants, and a thriving culture valuing partnership and sustainability. In fact, the backbone of Oregon’s renowned food culture is the land-use bill Governor Tom McCall signed into law in 1973 to protect high-value forests and agricultural land. This law, Senate Bill 100, is now used as a national model. Had it not passed, Oregon would be a different place. The fertile soil of Sauvie Island, the orchards of Hood River, the dairy pastures of Tillamook County, and the south-facing slopes of the Willamette Valley vineyards that have produced some of the best pinot noirs in the world would be rows of tract housing, strip development, and subdivisions. Most Oregonians understand, seemingly on a gut level, that protecting this land is desperately important, and the choices we make must reach further than our own back yards or bank accounts. [%image erin float=left width=400 caption="Erin Ergenbright (far left) participates in the Program with her Ripe colleagues."] Our country’s historic tendency has been to “get while the getting was good,” without giving any thought to the idea there might not be an endless supply, whether of buffalo, trees, or gold. But those who traveled the Oregon Trail and settled in the Willamette Valley weren’t cut from the same philosophical cloth as the California gold rushers. They weren’t as interested in the gamble, or the flash in the pan; they wanted to build something that would last. And on that sun-soaked, late-winter morning, watching John Paul shape the destinies of his 100-year-old vines, the literal illustration of one choice being inextricably connected to so many possible outcomes was making me fairly swoony. And looking around at the sun-flushed faces of people I’d now known and worked with for years, I realized how deeply I believed in what we were doing. But I’d been in the dark about a few things, and was not alone in there. Despite the Barnum-like hype surrounding Ripe, it was hemorrhaging money, but only Michael knew it. Three months after the Food & Wine article in which he’d sniped at Alice Waters, he was forced to tell investors he couldn’t make payroll for the company’s 95 employees. He left town that night, and the next day, all Ripe’s restaurants except clarklewis closed and the Hebberoys filed for divorce. And Michael’s end quote in Food & Wine now seemed prescient: “I’m not interested in having the career arc of a restaurateur,” he said. “I’m more defined by departures.” Even though 75 percent of restaurants fail, the collapse of Ripe was huge news — seemingly in direct proportion to the ardor it had received. It was like the Titanic going down, with Michael scurrying off in the lifeboat while all those who’d believed in his vision went down with the ship. People inside and outside the restaurant industry gossiped about it as if gorging on junk food, and food blogs were swamped with angry, snarky, and triumphant told-you-so missives. Even years later, the mention of Michael Hebberoy’s name still incites a certain amount of passion. But beyond money lost by farmers, purveyors, and investors, beyond people used and discarded or the sordid details that may or may not be true, what happened still stings because it revealed how naïve we were for wanting so badly to believe. Some of us felt duped and lied to by someone claiming that every participant in the conversation mattered. But I’ve since realized that dwelling on this specific, dramatic, and disappointing story is wasteful, a careless use of resources, in light of the many people involved in Oregon’s food culture whose lives and actions have reflected their belief in sustainability. [%image burner float=right width=400 caption="Members of the Ripe staff at Cameron."] And maybe Michael Hebberoy’s goal was never about sustainability, but instead about bringing people together in order to get them talking, to stir the pot, as it were. In that, he clearly succeeded. And many of the talented cooks and chefs of the fallen Ripe empire went on to receive national attention in new restaurants (though for the food rather than the theatrics); and in general, the conversation that continued long after the debacle has renewed our understanding of interconnectedness, and the necessity of supporting and partnering with each other. When I think of that morning at Cameron Winery, choosing the canes that would become next year’s fruit and the spurs that would direct the future of the vine, I think of the choices we make every day that may have a larger impact than we realize. Balancing a great vision with awareness of the greater good is no easy task, but one made easier if that abstract idea is instead focused on the specific people and places that form our community. And Oregon’s history makes clear how greatly our communities impact us, make us what we are; as a vine’s deep roots inform its wine’s terroir, our lives bear the thumbprint of the forces that have shaped it. p(bio). A co-founder of the loggernaut reading series, Erin Ergenbright is also the co-author of [%bookLink code=0060185201 "The Ex-Boyfriend Cookbook"]. Her essay [/articles/firstperson/eatingalone '"Table for One"'] was also published on Culinate. p(bio). C.J. French provided all the photos for this excerpt. Her work does not appear in Citadel of the Spirit._

burner, l

erin, l

john paul, l

reference-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l

promo-image, l