reference-image, l

(article, Mani Niall)

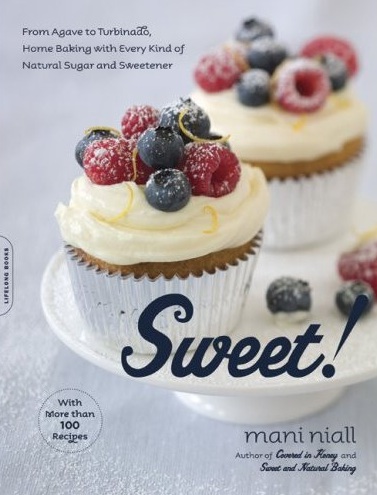

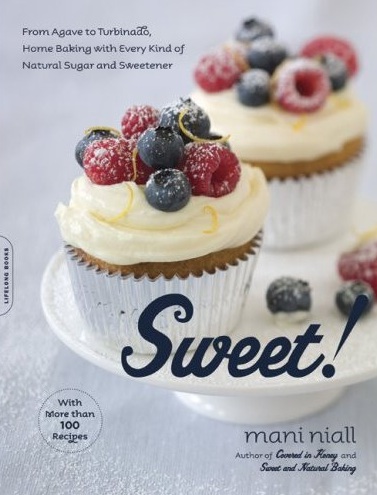

[%pageBreakSettings nobreak=true][%adInjectionSettings noInject=true] h3. From Chapter 1: Sugar and Your Kitchen The first sweetener was honey, which nature supplied via wild bees. For eons, outside of eating fruit, honey was the most uncomplicated way for humans to get the sweetness that their bodies craved. Then, probably in what is now New Guinea, around 6,000 BCE, people started cultivating sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum), a tropical, bamboolike grass that contained an irresistibly sweet juice. To get to the juice, the plant's stalk was cut down and the cane was chewed (you may have encountered sugar cane in some modern-day Southeast Asian dishes, such as Vietnamese chao tom). [[block(sidebar). h1. About the book and author After stints as a personal chef and caterer, Mani Niall opened a healthy Los Angeles bakeshop called Mäni's Bakery Café. Today he's an executive chef with Just Desserts, a commercial bakery in the Bay Area, and runs a food consultancy called Mani's Test Kitchen. Sweet! is a comprehensive survey of sugar and other sweeteners: what they are, how they're made, where they come from, how to shop for and store them, and, of course, what to do with them in the kitchen, from breakfast through dinner and dessert. Excerpt reprinted with permission of Da Capo Lifelong Press, a member of the Perseus Books Group (2008). ]] From there, the sugar-cane plant traveled to India, where it took to the hot climate. The Indians developed a process to extract, boil, and crystallize sugar-cane juice. Sugar established itself in Indian cuisine and culture. It was said that Buddha was born in Gur (today's Bengal), known as "the land of sugar," and gur is still used as a word for sugar in Bengalese and other Indian languages. These mounds of hard sugar remained a local product until Persians invaded India in 510 BCE, when King Darius wrote of a new find: "the reed which gives honey without bees." Persians were now the guardians of sugar production, and they closely held these secrets for over nine hundred years. Control over the sugar industry changed again in 642 CE, when the Arabs invaded Persia. The Arabs traveled far and wide to expand their empire, and in doing so, brought sugar to Spain and North Africa, neither of which had any Western influence to note. Sugar remained locked in Eastern culture until the Crusades, and wasn't mentioned in English until 1099. Until then, honey was Western civilization's only sweetener. (To this day, honey-rich gingerbreads and cookies remain European favorites.) The Crusaders came across the "sweet salt" in their efforts to bring the Holy Land, which was Arab territory, under their control. Sugar crystals were similar to the rare spices that were so important to European cooking and Europe's economy — expensive, and for the rich. As was the case with spices, obtaining them necessitated trade with the Eastern nations. Much of the sugar passed through the markets of Venice, and the Venetian wholesalers were notoriously tough. To help lighten the financial burden, sugar-cane crops were established in the warmest European regions, such as Portugal and Spain, and then in their colonies off the African coast. To this day, very sweet desserts are intrinsic to these areas' cuisines, as sugar was a local product that could be used with relative abandon (not to mention their being part of the Arabic influence in Spain). Sugar production and trade went through a monumental change with the discovery of the New World and its abundance of warm locales that would support the growth of tropical sugar cane. During his second voyage to Hispaniola (the island that today is Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Christopher Columbus stopped off in the Canary Islands for provisions, and acquired sugar-cane stalks. These were duly planted back home and the resulting crop thrived. Sugar was just one reason why the European powers strove to establish colonies in warm regions where it would thrive (the desire for tobacco and cotton and the quest for gold also played their parts), but it was a very important reason. Sugar cane does not cut, refine, pack, and ship itself, and the industry required workers — by the hundreds of thousands. When the Native Americans proved to be very susceptible to diseases carried by the Europeans, millions of Africans were enslaved and brought to work on sugar plantations. [%image feature-image float=right width=400 caption="A sugar-cane worker burning a cane field in Brazil."] The New World products created what historians call "the triangle trade." A boat would travel from a European port to Africa, laden with manufactured products to sell. Once the boat was emptied of its goods, African humans were bought as slaves. The boat sailed across the Atlantic to the next stop on the triangle, South and Central America, where slaves were put to work on sugar plantations. Finally, the boats were loaded again, this time with sugar and other New World goods to close the triangle with a voyage back to Europe (often with a stop in Boston), where those goods were sold to eager buyers. The Portuguese were the first to establish sugar plantations in the New World, in Brazil. When the Dutch invested in sugar plantations in the Caribbean Islands, sugar (and its by-products, molasses and rum) flowed into Europe. France considered the tiny island of Guadeloupe, which had fallen under British rule, so important to its economy that they traded the whole of Canada for its return. (Voltaire dissed Canada as "a few acres of snow.") Canada wasn't the only colony that was considered of little value to the Old World. When given a choice of where to spend their efforts and money, the Dutch chose the South American island of Suriname over New Amsterdam (now New York). While Europe clamored for more sugar, the Caribbean, especially San Domingue (today's Haiti), Barbados, and the various islands in the British West Indies, supplied it through the suffering of slaves. Over the years, mechanization improved to the point where less humanpower was needed, and the British government could afford to abolish slavery in 1838. [[block(sidebar). h1.Featured recipes]] The British upper classes were especially enamored of sugar. Most of it was stirred into tea, but when the industrial revolution mechanized sugar production and made sugar less expensive, jams, jellies, and candies could be produced cheaply, and this satisfied the sweet tooth of the masses, rich and poor. The next revolution in the sweet world took some time to take hold. In 1747, a German chemist isolated sucrose in a sweet white tuber, the sugar beet (Beta vulgaris). It took a while to take hold, but eventually sugar-beet factories sprang up in Europe to extract their sweet juice. The home-grown sugar was particularly useful to France during the Napoleonic Wars, when the British embargoed their Caribbean product. Today, beet sugar provides about 30 percent of world production of granulated sugar. Cane sugar is still king, but public interest in alternative sweeteners, from honey to agave, is strong. Also gaining momentum is the natural-sugars movement, with sugars that are grown according to fair-trade guidelines or are minimally processed. Now the world of sugar encompasses many varieties of sweeteners available in your local markets, so you don't have to restrict yourself to white granulated sugar unless you want to.

reference-image, l

feature-image, l

featurette-image, l

promo-image, l

feed-image, l